|

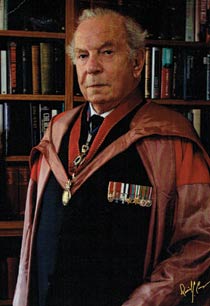

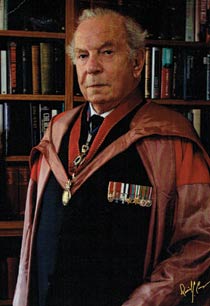

PROFESSOR SIR MICHAEL HOWARD OM CH CBE MC

formerly Coldstream Guards

In conversation with The Editor

|

Professor Sir Michael Howard is a Guardsman as well as one of the most distinguished historians of the post Second World War era. He served with the Coldstream Guards in the Italian campaign and was awarded a Military Cross. Returning to Oxford after the war, his first academic appointment was at King’s College London, where he was later invited to put his name forward to form a new department that would become known as The Department of War Studies. His wartime experience and the fact that he had co-written the regimental history of the Coldstream Guards had given him some useful grounding in the subject, but the department he was to create had a much broader remit than purely the study of military history. This was to be a multi-disciplinary department that acknowledged ‘War’ as a much wider subject than the conduct of battles and campaigns.

Michael Howard, 1938, aged 17 Michael Howard, 1938, aged 17 |

In the aftermath of the Second World War, and with all the new threats that emerged during the Cold War, it is perhaps not surprising that the need for such a department had been identified. War was now not just the business of generals and their armies; it impacted on all aspects of society, and at every level. ‘War Studies’ drew together disciplines and expertise that went well beyond the military conduct of war. The department that Michael Howard created some 60 years ago has become a world leader in the study of war, and his vision and influence still thrives there. In 2015, The Sir Michael Howard Centre for the History of War was opened in recognition of this considerable achievement.

Much of this preamble leads back to the opening months of the war, when Michael Howard was still a schoolboy at Wellington College, looking forward to going up to Oxford, but mindful that military service was somewhere on the near horizon. Neither the Royal Navy nor the Royal Air Force particularly appealed, and as he had friends from school joining the Army, this seemed the most attractive option. As he told me when we met just before Christmas at his home a few miles north of Hungerford, in the valley of the River Lambourn, he had no desire to drown at sea or be shot down in an aeroplane. Many of his friends had told him ‘the Army is not only much better company but was also much safer because if you just dug a hole everything would be alright’.

Then, which part of the Army to join? Nearly 80 years on, and Michael Howard is precise as he poses and then asks the question ‘Why the Coldstream?’ At Oxford, where he spent a while before joining up, he had met other undergraduates who were bound for the Brigade of Guards, and the Adjutant of the OTC, a Coldstreamer, had suggested the Regiment. But the real clincher was the Regimental March. ‘I reckoned that a regiment that had a regimental march by Mozart was a much more civilised establishment than anywhere else’. He never for a moment regretted his decision, and he ‘still purrs’ when he hears the music, at which point he gave me a short and very clear rendition of the opening words of Figaro’s wonderful opening aria ‘Non piu andrai, farfallone amoroso’. In his memoirs, he recalls his interview with the Regimental Lieutenant Colonel, not daring to give Figaro as his reason for joining the Regiment. Years later they met again at a regimental dinner, and the Regimental Lieutenant Colonel roared with laughter when Michael told the story. ‘My dear boy, why didn’t you tell me? We would have been delighted’.

Regimental Sergeant Major ‘Tibby’ Brittain,Coldstream Guards |

His time at Wellington and at Oxford, where he had been a member of the Officer Training Corps, provided a useful grounding for military service, and the fact that many of his school and university friends were also bound for the Brigade of Guards was an added and shared comfort. But perhaps nothing could have prepared him for his first full exposure to the ways of the Guards, in the shape of Regimental Sergeant Major ‘Tibby’ Brittain, a legendary Guardsman and a ‘terrifying man, I have never been more frightened in my life’. His voice, his appearance, and presence on the parade square, seemed to reach everywhere and everyone. ‘Almost the first time on parade, this formidable figure, shouting out from some distance, and then suddenly he was pointing his pace-stick and it seemed to be directly at me, and then he advanced on me, shouting louder and louder’ only to pounce on the recruit standing next to him. It was a memory that has stayed with him, and on his many visits to Sandhurst over the years, he has been reminded of just how important the non-commissioned officers are. They are, without question, ‘the backbone of the Guards’, and there was some virtue in being more frightened of them than the real enemy.

Would Michael Howard have joined the Army had there not been a war? Again, his answer is precise. No, ‘never in a single moment would I have considered it. No Army connections at all. My mother’s family were German Jews and my father’s were Quakers’. When he was at Wellington, although surrounded by friends from Army families, he was clear that the military life was not for him. But then, here he was, during a war, as a young officer in the Coldstream Guards. Under the circumstances, it was a most tolerable place to be, and a part of his long life that Michael Howard does not regret. And his time in the Brigade of Guards has left indelible memories, so much so that when he came to publish his memoirs in 2008, he chose to call them Captain Professor, a life in war and peace, using the title used by his old Regimental Headquarters when corresponding by post: ‘Captain Professor M E Howard’.

Michael Howard was commissioned in December 1942, and while waiting to join the 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards, he spent a short time doing Public Duties with the Holding Battalion in London. Since it was wartime, the Guardsmen were wearing battledress rather than tunics and bearskins, but the experience was still ‘great fun…, and although one didn’t join the Army to have fun, it was nevertheless wonderful for morale to do Public Duties’. He remembers the sergeant majors reminding those on parade that they were Guardsmen and ‘should behave like a Guardsman and dress like a Guardsman’ with the added factor of ‘a large public audience’ watching their every move. ‘An element of the “stage” enters into it – a bit of showing off’, something that ‘separates Guardsmen from other troops, the realisation that they are on display, wherever they are and whatever they are doing, and something they must never forget’.

|

Officers at Castigione, winter 1944-45.

Michael Howard on far right |

This was an aspect of the Brigade of Guards that, he recalls, came up time and again. In Italy, he remembers ‘one particular incident, we were in the mountains north of Florence, in pretty close contact with the Germans, living under extremely primitive conditions, in slit trenches, in heavy rain. And then, after about a week, we were relieved. We were marched and put in to trucks and taken back to Florence. And when we arrived in Florence, the Drill Sergeants were there. “You will be on parade tomorrow morning at 8 o’clock. No nonsense”. We had to clean our kit and be on parade’.

His active service had begun in September 1943. The 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards had spent time in Tripoli, reconstituting after the North African campaign, but when Michael and others arrived from England, the Salerno landings had just taken place and so ‘We joined literally on the beaches’, as the fighting was taking place a short distance inland. The last major German attack onto the beachhead had just been repelled by the Gunners and naval gunfire, and now the action had shifted to the high hills and woods that surround Salerno like a great amphitheatre.

When Michael reached the Battalion shortly after arriving on the beach, he found them to be in ‘not in a bad mood at all, they had had a tough two or three days, but not nearly enough to bash them about’. He was soon placed in command of a platoon and sent out on a patrol. ‘I had never seen any of the men before. They had all come from Egypt and had never been in that kind of battlefield before. We got totally lost, bumped into the Germans where we weren’t expecting to find them, and then got back and reported’ the results of the patrol.

Quite an opening experience for a young officer just arrived from England, to be then followed by 10 days of sustained fighting which included the attack on Hill 270 on 25th September 1943 for which Company Sergeant Major ‘Misty’ Wright, Coldstream Guards, was later awarded a Victoria Cross. Just before this, Michael Howard had led a diversionary night attack which he describes vividly in his memoirs, an account that really does evoke a sense of what it must have been like: the utter confusion, the ‘fog of war’, the ‘howls and groans and screechings in the air’ of the shells, and the ghastly aftermath in which he and his platoon buried the German dead at dawn ‘in the first grey hints of light’. We didn’t talk about that attack during our conversation in late 2018, but the account is there in Michael’s memoirs. It is an extraordinarily powerful piece of writing, and although he makes no mention of it here, it was this battle for which he was later awarded a Military Cross.

The fighting at Salerno had taken its toll on Michael and others in the Battalion, and he was to spend the next six months recovering from malaria, first in hospital, then convalescing and serving with the Guards Reinforcement Training Depot. He re-joined the Battalion as it was approaching Florence in the summer of 1944, following the battles around Monte Cassino, an experience he counted himself lucky to have missed, although there was still plenty of fighting to come.

Major General Sir George Burns, who commanded 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards during the Italian campaign Major General Sir George Burns, who commanded 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards during the Italian campaign |

We talked about Guardsmen that had made a special impression. ‘Tibby’ Brittain was the first, but in Italy it was the Commanding Officer, George Burns. Michael recalled one occasion when ‘we had had a nasty stonk [A ‘stonk’ is a WW2 expression for artillery fire’] put down, a very heavy stonk indeed. We were just pulling ourselves up when George Burns appeared, pipe in one hand, walking stick in the other, beaming at us. And from the moment he appeared, everything seemed to be alright. It was astonishing what that man did. That made me realise what Clausewitz said was absolutely right. What really matters in an army is morale and moral strength and fibre. Once George appeared, everything was ok’.

The Italian campaign was a long and gruelling one, in which no one experienced that great sense of victory that must have been much more evident in NW Europe. Following the fall of Rome and D-Day in Normandy, both occurring on the same day, 6th June 1944, there had been the optimistic hope that the fighting would be over quickly. But it was not to be. Progress was painfully slow as the British and Americans ‘slogged’ over the mountain ranges and German defences. Michael Howard recalls reaching Florence in September 1944, ‘looking up at yet another mountain range, and thinking, we have to get through that - morale was not good’. And then the following spring ‘we looked down on the Po Valley with the Alps beyond and Germany did not seem any closer’.

The Germans kept on fighting until the end, ‘and they were very good at it, withdrawing in very good order, causing us the greatest amount of difficulty’ before ‘just fading into the mountains’ once they knew that they had been defeated on all other fronts. And beyond the Po River, over which the Germans had withdrawn, Michael recalls fields full of abandoned horses, realising for the first time that the Wehrmacht was still a largely horse-borne army. ‘We had some fun with the horses, but with the Germans now gone, we were told “sorry the next lot of enemy is the Yugoslav partisans, and I remember writing a rather despairing letter home that we have just finished World War Two and without any pause we seem to be getting into World War Three’.

Michael Howard spent the last few months of the war with the 2nd Battalion, the 3rd Battalion having left Italy in the spring of 1945. He recalls an ‘interesting difference in style between the two’. The 3rd Battalion still wore desert boots and mufflers, fur coats and all the ‘panache of the desert’. The officers messed together in company messes, and rarely mixed with other officers in the Battalion. By comparison, the 2nd Battalion had served back in England following Dunkirk, and before deploying to North Africa, and ‘were all “dead reg” and all the officers knew each other. They were all Coldstream Guardsmen, but each battalion had its own distinctive style, a reflection of its wartime experience.

Captain Michael Howard MC Captain Michael Howard MC

|

Michael Howard was demobbed at the end of the war and was very happy to return to civilian life and to Oxford where he completed his degree. Back at Christ Church, he was approached by John Sparrow, another former Coldstreamer, and asked to collaborate on a Regimental History of the Coldstream Guards in the Second World War. It proved to be an invaluable experience, because writing regimental history is not easy. For example, he soon concluded that one ‘should never trust an eyewitness, not even yourself’. Looking back, he cannot think of a better way for an historian to start writing than to ‘write a little military history’, mindful, of course, that regimental history can be unreliable in some respects, because of the tendency to ‘smooth-over’ difficult events.

Professor Sir Michael Howard, in his study Professor Sir Michael Howard, in his study |

Our delightful conversation had come full circle. We began in those early days of the war, when Michael Howard had still been at school and then briefly at Oxford, and we concluded with him completing his degree and writing his own regiment’s wartime history. A distinguished wartime career was to be followed by a distinguished career as an academic. But in another sense, this is just one very long and very distinguished career that began on the parade ground with ‘Tibby’ Brittain, and continued through King’s College London, to Oxford, where Michael Howard was first Chichele Professor of the History of War, followed by the Regius Professor of Modern History and finally Yale, as Professor of Military and Naval History. Along the way, and amongst many other achievements, he has written widely, lectured around the world, advised politicians, and helped to establish the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

It was at Salerno, and the manner in which he later described his time there, that Michael Howard also realised that Clausewitz was right about war. They had both experienced the sharp end, and a modern understanding of Clausewitz has benefited greatly from Michael Howard’s translations and interpretation of his seminal work On War. At Salerno, for the first time, he experienced many of the aspects of war that Clausewitz had written about in the early 19th century and, serving with George Burns, he saw how a certain kind of leadership can raise the morale of tired and frightened soldiers, another key factor in war identified by Clausewitz.

Michael Howard never intended to join the Army or the Brigade of Guards but did so for good reason, nearly 80 years ago. He was a Guardsman then, and he is still a Guardsman now.

|

|

Michael Howard, 1938, aged 17

Michael Howard, 1938, aged 17

Major General Sir George Burns, who commanded 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards during the Italian campaign

Major General Sir George Burns, who commanded 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards during the Italian campaign

Professor Sir Michael Howard, in his study

Professor Sir Michael Howard, in his study