|

BURNABY’S DEADLY WEAPON

A recent addition to the Household Cavalry Museum’s collection

by Christopher Joll

formerly The Life Guards

|

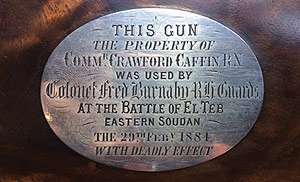

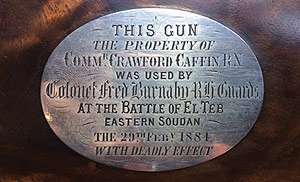

In the entire history of British gun-making there has only been one shotgun at the centre of a major parliamentary row. The gun in question, now in the collection of the Household Cavalry Museum thanks to the generosity of Lieutenant Colonel (Retd) Anthony Potter, a lineal descendant of its original owner, was made by E Paton of Perth, London & Inverness, Gunsmiths to HRH The Late Prince Consort. It has the redolent serial number,1815, and an engraved silver plate on the stock stating that the gun is the property of Commander Crawford Caffin RN.

Burnaby’s gun

|

So, what generated all the heat in the House of Commons in mid-March 1884? In a nutshell, the Tory Opposition of the time was determined, whenever it could, to embarrass the Gladstone-led Liberal Government on the vexed subject of the Sudan, then an Egyptian-run province of the Ottoman Empire which, as a preliminary to an armed march on Constantinople, had been over-run by the Muslim fundamentalist forces of Muhammad Ahmad, the self-proclaimed Mahdi or Chosen One. Whilst there was scant British concern for the fate of the Sudan, Egypt was another matter altogether. This was because, were it to fall to The Mahdi on his murderous pilgrimage to the Hagia Sophia mosque in Constantinople, there would be a significant risk to the control of the strategically important, Anglo-French owned, Suez Canal. This risk vexed the Tories to a very considerable extent and gave them a handy weapon with which to ambush the Liberals at every opportunity. Tory sniping at the Government on the subject of the Sudan was intensified following Gladstone’s reluctant decision to, in effect, abandon the country by tasking Major General Charles Gordon with the limited task of evacuating non-Sudanese nationals from Khartoum.

Tory sniping evolved into volley fire in the wake of the massacre of a British-led, 7,000 strong force of the Egyptian Gendarmerie by the troops of Osman Digna at the First Battle of el Teb on 4th February 1884. El Teb was a Mahdist stronghold in north-eastern Sudan, uncomfortably close to the Suez Canal, and Osman Digna was an Egyptian slaver who had been put out of business by the British, as a consequence of which he had become a keen supporter of The Mahdi. The disaster at el Teb, on the doorstep of Egypt and uncomfortably close to the southern approach to the Suez Canal, led to Gladstone’s even more reluctant decision to divert to Suakin (a British-held port within easy reach of El Teb) 2,500 British soldiers, under the command of Major General Gerald Graham VC, which conveniently happened to be sailing up the Red Sea, en route home from India. This Brigade-strength force comprised units of the Gordon Highlanders, the Black Watch, the Royal Irish Fusiliers, the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, the York & Lancaster Regiment plus the 10th and the 19th Hussars, who borrowed their mounts from the defeated and demoralised Egyptian Gendarmerie. This ad hoc British Army Brigade was bolstered with a hastily assembled Naval Brigade, under the command of the ‘fighting Admiral’, Rear Admiral Sir William Hewett VC, comprising 162 matelots and 400 Royal Marines armed with two 9-pounder naval guns, three Gardner machine guns and three Gatling guns, drawn from HMS Briton, Carysfort, Decoy, Dryad, Euryalas (Hewett’s Flagship), Hecla, Humber, Ranger and Sphinx, all anchored at the port of Suakin.

After months ‘on the back foot’, newspaper reports of the Second Battle of el Teb, fought on 29th February, gave the Liberals what they thought was a chance to return fire on the Tories from the moral high ground. The facts of the matter, as reported in The Times and elsewhere, were straightforward. The battle had opened with an advance ‘in square’ by Graham’s troops towards Osman Digna’s headquarters at the fortified village of el Teb. Two hundred yards from these defences, the square was ordered to halt, and the Naval Brigade’s machine guns were deployed to supress the fire from the enemy in the open and on the fortifications. This was followed by a conventional, if rather costly cavalry charge by the Hussars against Osman Digna’s men in front the village, after which the square resumed its advance to the barricades where it formed into line, fixed bayonets and charged. It was at this point that Colonel Fred Burnaby, who was at the time on leave in the Sudan and looking for action, entered the story and, inadvertently, provided the Liberal Government with a weapon with which to attack the Tories.

Burnaby was a former and failed Tory parliamentary candidate, long-term scourge of the Liberals and nominally Commanding Officer of the Royal Horse Guards (The Blues). On Graham’s arrival at Trinkitat, Burnaby had wangled himself a role on the Staff as a ‘temporary Intelligence Officer’. Despite being in the centre of the square with the rest of the Staff, Burnaby, whose horse had been shot from under him, was the first man to reach the enemy’s defences at el Teb where, with a shotgun borrowed from Commander Crawford Caffin RN, he clambered onto the parapet.

He was immediately surrounded by half-a-dozen of the enemy whom he dispatched by firing both barrels of his Paton-made shotgun, which he’d loaded with pig shot, at point-blank range. Burnaby followed up this slaughter by clearing out Osman Digna’s forces in an adjacent stone building. When he ran out of cartridges, he used the shotgun’s stock as a club until he was wounded in the arm. About to be killed by tribesmen, he was saved by the point of a Highlander’s bayonet. Accounts differ as to the number of Osman Digna’s men whom Burnaby dispatched to Paradise, and the tally of shotgun cartridges he had needed to achieve that score. However, Commander Caffin would later assert that Burnaby had killed thirteen men with twenty-three cartridges and that is the count which has entered the history books.

Back in England there was outrage in the liberal media: ‘Colonel Burnaby’s massive form was the first I saw over the parapet, firing with a double-barrelled gun into the little cluster of rebels’ whinged The Observer on 2nd March.

This was countered the following day by the more jingoistic British newspapers, which hailed Burnaby as a hero: ‘Colonel Burnaby did good work with a double-barrelled gun and slugs, finishing ten men with twenty cartridges’ thundered The Times, to which The Standard added: ‘With the double-barrelled fowling piece he [Colonel Burnaby] carries, he knocks over the Arabs who assail him’.

A two-pronged attack on the Tories by the Government started on 15th March when Sir Charles Dilke MP, a Liberal Minister and President of the Local Government Board, made a speech in the House of Commons in which he both questioned Burnaby’s presence on Graham’s Staff and disparaged his actions at el Teb.

On the following Monday, 17th March, the Tories went on the counter-attack in Parliament, as Hansard reported:

Lord Randolph Churchill [Conservative]: ‘I want, with the permission of the noble Lord the Secretary of State for War, to ask him a Question [which]… concerns the honour and character of a gallant officer. The Question is this - whether it is not an invariable and immemorial rule of the British Army that any British officer on leave, who finds himself in the neighbourhood of British Forces engaged in military operations, is bound to place his services at the disposal of the officer commanding those forces? …’

The Marquess of Hartington [Liberal & Secretary of State for War]): ‘I am not aware of any such rule as that referred to by the noble Lord; but I have not the least doubt that any officer on leave, finding himself in the neighbourhood of British Forces engaged in military operations, would offer his services to the officer in command….’

Lord Randolph Churchill: ‘… I wish, further, to ask whether the noble Lord is aware that his Colleague, the President of the Local Government Board, stated in this House, on his own knowledge, that Colonel Burnaby was under no necessity to take part in military operations?’

Sir Charles Dilke: ‘I must entirely contradict that. What I said was, that Colonel Burnaby was under no military necessity to take part in the military operations by firing on the Arabs with a shotgun.’

This was the nub of the matter and led to an extended exchange of increasingly heated questions and answers across the floor of the House of Commons, most of which were focused on the allegations that Burnaby’s use of a shotgun had been, at best, inappropriate and, at worst, contrary to the ‘usages & practices of war’. The fire only died down when Lord Hartington stated, in answer to a question from Mr Buchanan:

‘… I may, however, add that, even assuming that the newspaper accounts of the matter are accurate, I am not aware that Colonel Burnaby did anything contrary to the usages of war. I do not, therefore, propose to take any further steps in the matter.’

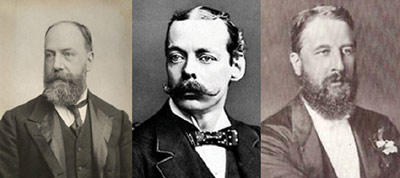

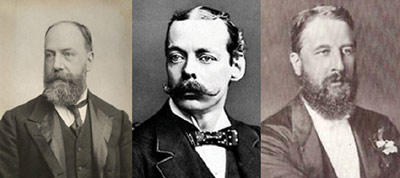

Left-to-right: Sir Charles Dilke, Lord Randolph Churchill,

Left-to-right: Sir Charles Dilke, Lord Randolph Churchill,

and the Marquess of Hartington |

So, who were the players at the centre of this over-heated parliamentary spat?

Beyond a famous portrait of Burnaby as a twenty-eight-year-old officer in the Royal Horse Guards by Tissot (now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery) and his grisly end at the Battle of Abu Klea in 1885 (an event immortalised by Sir Henry Newbolt’s poem, Vitai Lampada) the shotgun-toting Blue at el Teb is, today, not widely known beyond the barracks of the Household Cavalry and students of nineteenth-century British imperial history. The owner of Burnaby’s controversial shotgun, Commander Crawford Caffin RN, rates barely a mention in accounts of the battle or the annals of the Royal Navy.

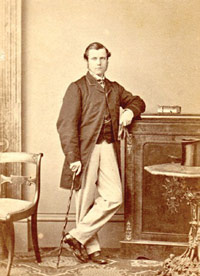

On the face of it, Colonel Frederick Gustavus Burnaby (1842-1885) was the quintessential Victorian hero: Flashman without the dubious moral compass, although the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, whilst noting that Burnaby was married, casts doubt on his sexuality. As a young man he was six feet four inches in height, had a forty-six-inch chest, weighed twenty stones and was reputed to be able to bend a poker with his bare hands, do gymnastics with a 1.5 cwt dumb-bell and carry a pony, presumably of the Shetland variety, under each arm. After school at Harrow and in Germany, his father bought the seventeen-year-old giant a commission in the Royal Horse Guards (The Blues). This was actually a poor choice for a man of action, as The Blues’ principal preoccupations since the Battle of Waterloo had been to provide Mounted Escorts for the Sovereign and to adorn the salons of London Society.

Captain Frederick Gustavus Burnaby, in Blues’ Stable Dress, painted in 1870 by James Jacques Tissot

National Portrait Gallery

|

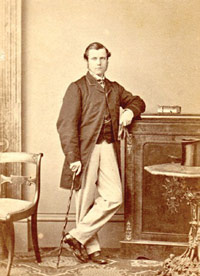

Crawford Caffin as a young man

|

It wasn’t long before young Burnaby tired of poodle-faking in the capital of the Empire and sought more energetic outlets for his adventurous nature. So, in the six months of the year when he wasn’t dancing attendance upon the monarch or making polite conversation in Mayfair drawing rooms, he travelled widely and often dangerously. His wanderlust took him to Central and South America in the 1860s; to North Africa in 1868, by which time he had advanced to the rank of Captain; in 1873-4, he travelled to war zones in Persia and Spain with his friend Lieutenant Colonel Valentine Baker, the Commanding Officer of the fashionable 10th Hussars; and, at the end of 1874, he helped Colonel Charles Gordon, then on his first stint as the Governor of Sudan, to suppress slavery in the region. To complete his adventures, during the winter of 1875-6 Burnaby rode from European Russia to Khiva in Central Asia, a three-hundred-mile journey that was extremely dangerous, not because of savage tribesmen along the way but because of the extreme cold on the steppes. His constitution was, as a result, badly damaged and, by the time of el Teb, Burnaby - although only forty-one years old - was grossly over-weight and suffering from chronic lung and heart disease, either of which could have killed him at any time.

During each of his expeditions, Burnaby sent regular reports to The Times and later published accounts of his travels, tales which became best sellers and established his reputation as an intrepid Victorian adventurer. Despite these extended periods in the wilds, a daring cross-Channel trip in a hot air balloon, and a brief foray in 1879-80 as a newly promoted major into the equally dangerous world of politics, in 1881 Burnaby was appointed to command of The Blues, then based in Windsor. Although very popular with the rank-and-file, he was disliked by his brother officers who despised his continuing journalistic output which had moved from travelogue to Society gossip.

In 1882, after an interval of sixty-seven years without active service, the three Regiments of the Household Cavalry were called upon by the War Office, despite Queen Victoria’s opposition, to provide a Squadron each for a Household Cavalry Composite Regiment as part of Lieutenant General Sir Garnett Wolseley’s Expeditionary Force tasked with quelling an insurrection in Egypt, led by Colonel Urabi, which threatened the ownership and control of the Suez Canal. Due to his unpopularity in Whitehall, Burnaby was not, as he had hoped, given command.

By way of compensation, but without War Office permission and whilst still nominally in command of The Blues, Burnaby took an extended leave of absence from his Regiment and attached himself to the Egyptian Gendarmerie under command of his old friend, the by-now disgraced Lieutenant Colonel Valentine Baker. Luckily for his reputation, Burnaby did not take part in Baker’s disastrous first action at el Teb but, with the arrival of Graham’s force, both Baker and Burnaby saw the opportunity for some action with real soldiers and, as already related, joined the General’s Staff. It was either in the staff mess tent at Trinkitat, or at a Staff conference prior to the advance on el Teb, that Burnaby probably met Commander Crawford Caffin RN (1845-1891) the only son of Admiral Sir James Crawford Caffin KCB.

Crawford Caffin joined the Royal Navy as a Midshipman in 1858. He was promoted to Sub Lieutenant in 1864 and to Lieutenant in 1865. In September 1877, whilst commander of the schooner, HMS Beagle, Caffin arrived off Tana Island in the New Hebrides, following the murder by natives of a Mr Easterbrook, a British copra trader. There was talk at the time that Easterbrook had been murdered for interfering with a native woman; whether or not that was true, a search failed to find the murderer, but an accomplice was discovered and confessed to his role. This was crime enough for Caffin, who convened a drum-head Court which ordered that the man be hanged from the fore yardarm of the Beagle. Lieutenant Caffin’s action prompted an outcry amongst the liberal elite, led (inevitably) by Sir Charles Dilke in the House of Commons. In January 1878, Mr W H Smith, First Lord of the Admiralty in the Tory Government of Benjamin Disraeli, after confirming the execution, stated in answer to a question from Dilke:

‘… Mr Layard, Her Majesty’s Consul at Noumea… recommended Commodore [Hoskins] to demand that ‘the murderer should be required from the tribe, and hung at the yardarm as a warning to others’. Commodore Hoskins ordered Lieutenant Caffin… that if, after inquiry, he should be fully convinced that it was not the misconduct of Easterbrook that led to his being murdered, he was to cause the murderer to be executed according to judicial forms in the most public manner possible… As regards the competence of the officer to take these measures, the islands in question not being under the jurisdiction of any competent Court of any civilized country, this was the only course open for the punishment of such crimes. Only a short time ago for such a murder the course would have been to bombard the village and destroy it, which would have occasioned the loss of many innocent lives’.

Despite this parliamentary whitewash, the Admiralty ruled that future executions aboard Her Majesty’s ships were ‘undesirable’. The whitewash notwithstanding, the incident prejudiced Caffin’s promotion to Commander which only took place in 1879, a belated event which was welcomed by the Army & Navy Gazette. During the Anglo-Zulu War of that year Caffin commanded the Royal Navy’s transport service in Natal and, at the end of the conflict, was responsible for taking the defeated Zulu King Cetshewayo to England.

Caffin reprised his transport job in Alexandria during Wolseley’s suppression of the Urabi Revolt of 1882 and, two years later, whilst in command of HMS Sphinx at Suakin, he was, as related, seconded to the staff of the Naval Brigade attached to Graham’s force. Although, like Burnaby, Caffin should have remained with his fellow staff officers during the battle, the History of the Royal Navy by Sir William Clowes (1897) records that, at 1400hrs, the Commander - without the benefit of his shotgun but in the company of the ‘Fighting Admiral’ - was involved in the final assault on the enemy’s last position. For this Caffin received the Khedive’s Bronze Star, the Khedive’s Order of Medjidieh (3rd Class) and the clasps ‘Suakin’ and ‘El Teb’ to add to his existing Egyptian campaign medal.

In the aftermath of el Teb, Burnaby returned to England with the official Dispatches and his arm in a sling. He received a hero’s welcome in the Tory press and the London salons. Meanwhile, Caffin returned to his ship. The following year, Burnaby was once again in the Sudan, as part of Wolseley’s Nile Expedition to rescue General Gordon who was besieged in Khartoum; he was killed en route aged forty-two at the Battle of Abu Klea in circumstances that are still controversial. Three years younger than Burnaby, Caffin died aged just forty-six in Nice on 16th March 1891, having retired from the Navy the previous year for reasons of ‘ill-health’ according to the Nice Gazette.

It is a neat piece of historical symmetry that both the owner and the handler of the Paton shotgun, used ‘with deadly effect’ at the Second Battle of el Teb, died young, were men of action, and the subjects of political rows in the House of Commons led by Sir Charles Dilke. Whilst Britannia continues to make the finest sporting guns in the world, sadly she no longer produces men like Caffin and Burnaby.

This article is adapted from a profile of Colonel Fred Burnaby to be published in Britannia’s Guards: The Heroes & Villains of the Household Division by Christopher Joll & Anthony Weldon. The author is grateful to the Trustees of the Household Cavalry Museum and to Lieutenant Colonel (Retd) Anthony Potter for permission to use material from the Museum and Caffin archives.

|

|