Home | About Us | Subscribe | Advertise | Other Publications | Diary | Offers | Gallery | More Features | Obituaries | Contact |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

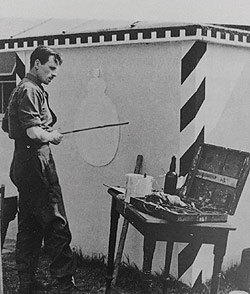

Around 75 years ago, at opposite ends of Britain, two artists were hard at work brightening up their austere wartime surroundings, one in the name of comfort, the other in the name of the Lord. Rex Whistler’s officers’ mess portraits and murals on Salisbury Plain are among his lesser known works, largely because so little evidence remains today; and Domenico Chiocchetti’s Italian Chapel on the Orcadian island of Lamb Holm is one of the UK’s (and Italy’s) hidden artistic gems, largely because it is so far away. I have always been meaning to put pen to paper about Whistler’s work at Codford, but a holiday to Orkney this summer spurred me into action to write about these rare and inspiring works of art.

After its defence of Boulogne and subsequent evacuation from Dunkirk in 1940, 2nd Battalion Welsh Guards spent over the next three years in England training and waiting for its call-up to the front. That time came finally in 1944 with the Normandy invasion and, shortly after, Whistler’s death in Caen on 18th July. It was during those years in England, while he was based at Codford, that Rex had the opportunity to paint extensively and complete most of his wartime works.

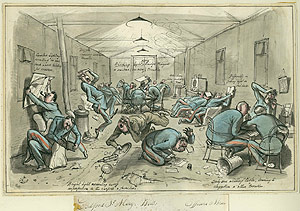

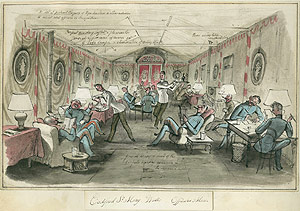

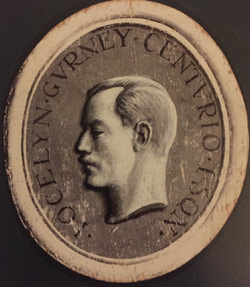

Rex put his idea on paper, producing humorous sketches of ‘The ante room as it was’ and ‘The ante room as it might be’. Both are annotated with comments criticising the décor in the former and making improvements in the latter. While the ‘might be’ sketch was just a whimsical suggestion, the officers were so impressed that they persuaded the Commanding Officer to allow Rex to spruce up the mess beyond all recognition. With the assistance of an able Guardsman, he painted striped poles and swags of fabric to transform it into an elaborate rococo tent. In the ante room he painted old masters with trompe l’oeil gilt frames onto the walls and in the dining room he hung portraits of his fellow officers, painted on oval pieces of plywood in the style of Roman bas-relief sculptures.

When the Italian POWs returned home in 1944, Domenico stayed behind to finish his brilliant scheme. He returned to restore it in 1960 and it was restored again in 2015 by an Italian artist who had previously worked on Michelangelo’s masterpiece in the Sistine Chapel. Today it is one of the go-to destinations for tourists visiting the Orkneys - mostly coach-loads of American tourists off cruise ships. I’d like to take this opportunity to plug the Orkneys for those that haven’t visited: military history at the Italian Chapel; naval history from both world wars; Stuart, Viking and Neolithic history with ruins and excavations all over the islands. And if you’re in that part of the world, a visit to the Queen Mother’s Castle of Mey is a must.

When 2nd Battalion Welsh Guards moved from Codford to Yorkshire at the end of 1942, the Coldstream Guards very gratefully took over their painted mess. Rex painted a Coldstream capstar on the outside before he left, replacing the Welsh Guards leek he’d painted there before. But the hut was dismantled after the war, leaving no remains except the portraits. They were sent to Regimental Headquarters for safekeeping, and returned to the officers’ families in 1962. My grandfather, Lieutenant Colonel Jocelyn Gurney DSO MC*, was one of the fortunate sitters, as the then Number 2 Squadron Commander (not company, because the Battalion was armoured). My family is lucky to still have the portrait today, one of only three known to still be in existence. If any readers know of the whereabouts of any others (in addition to those of Majors Jim Windsor Lewis and Timothy Consett) please do let the author know on fobwells@hotmail.com.

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||