|

AN INTERVIEW WITH ACADEMY SERGEANT MAJOR

(WARRANT OFFICER CLASS ONE) RAY HUGGINS MBE

Formerly Grenadier Guards

by The Editor

|

Anyone who was an officer cadet at Sandhurst in the 1970s will remember Ray Huggins. Like me, they won’t just remember his towering presence on the parade square and his charismatic style, but also what he actually said to them. I recall his words almost verbatim, when he addressed Standard Military Course No 10 the evening before we were commissioned on 6th March 1976.‘Gentlemen…. you have now entered the top five percent of the nation’, an alarming thought for a young man of 20, ‘and with that comes responsibilities’ … even more alarming. And then, following a pause, he said ‘Gentlemen, I would not wear jeans to do my gardening in, and I never want to see any of you gentlemen wearing jeans’. I heeded his advice 42 years ago, conceding, when I met him at the Royal Hospital in early December 2017, that it took a very long time before I did purchase a pair. Ray Huggins laughed, and his eyes twinkled. ‘Did you see that report in the newspapers recently about some celebrity who had paid $700 for a pair of jeans?’ I assured him that mine were rather more modest!

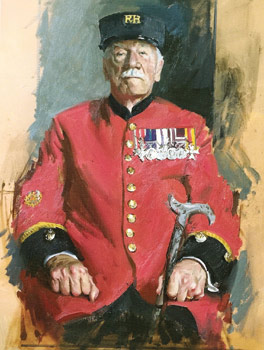

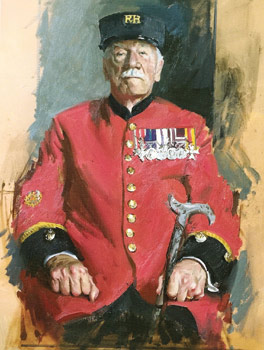

Ray Huggins, December 2017

Ray Huggins, December 2017 |

I arrived early for the interview, making my way to the In-Pensioners’ and visitors’ café not for far from the London Gate where we had agreed to meet at 11.30am. When I returned, a few minutes’ ahead of time, there was Mr Huggins, sitting to attention on the bench by the guardroom, arms outstretched and hands resting on his knees. Although I had briefly seen him at the Guards Depot in the late 70s, this was the first time we had exchanged words since September 1974, when I asked his permission to ‘fall out’ at the end of the ‘Passing off the Square’ inspection at Sandhurst. Now in his 90th year, Mr Huggins immediately stood to attention, and escorted me to his small but comfortable ‘bed-sit’ where we talked for the next 90 minutes.

Ray Huggins wanted to join the Guards from the age of 9, when an aunt took him to London and he saw the Guardsman on sentry duty outside St James’s Palace. ‘That did it for me’, he told me. He joined the Grenadier Guards, aged 17, just after the end of the war. He had tried to join when he was 16½, but an eagle-eyed recruiting sergeant spotted him, and he had to wait another six months. His father had served in the First World War, and in 1942, just three weeks short of him passing beyond the upper age limit for conscription, he was called up. He was offered a commission in the Pioneer Corps, but chose the Royal Army Service Corps, working on the Pipeline Under the Sea (PLUTO) for the Normandy campaign. A publican in Wilmslow, Cheshire, he left his wife and 14-year-old son to run the pub, and it was here that the recruiting sergeant remembered Ray, pulling pints behind the bar.

Although the war was over by the time Ray Huggins arrived at Fox Lines, not far from the main camp at the Guards Depot, Caterham, much of the wartime training regime was still in place. He recalls Sergeant Clutterbuck with his poker, hitting recruits on their tin hats to simulate grenades, and he did not actually enter the Guards Depot itself until some years later, when he returned as a superintending sergeant.

Ray Huggins joined 4th Battalion Grenadier Guards in Hamburg in 1946. The place, he said ‘was rubble’, and one of the less pleasant tasks given to the Grenadiers was to guard the internment camp at Neuengamme. A former concentration camp run by the SS, this was where nearly 43,000 prisoners had perished during the war, and now the Grenadiers guarded their SS captives, the former camp staff at this ghastly place. Ray Huggins, 18 years of age at the time, recalls the experience: seeing the SS soldiers digging the garden and preparing for their kit-inspections. His Company Commander was Dickie Rasch, and the Company Sergeant Major, Norman Mitchell, is also an In-Pensioner at the Royal Hospital.

The following year, 1947, Ray Huggins, now in The King’s Company, was part of the Guard of Honour for the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and, at 6’1” in height, he was the shortest Guardsman in the Guard! Then came Palestine in 1948, with the 1st Guards Brigade in Haifa, the last British troops to withdraw following the decision to end the British mandate. It was neither an easy or pleasant task, given the assurances that the British had given separately to both the Arabs and the Jews. Amongst the mayhem and fighting that Ray Huggins witnessed, he recalled one event with perfect clarity. He remembers an ‘absolutely gorgeous’ woman walking towards him at a roadblock, but fortunately he was not fooled by her striking looks; she was carrying a German Schmeisser machine-gun!

During his time with the Grenadiers, Ray Huggins served in many other places that have become only a memory for the British Army: Libya, Berlin, the Southern Cameroons, to name a few. In 1966 he was promoted to Warrant Officer Class One, serving first as Regimental Sergeant Major, Old College, Sandhurst. It was here that he saw the old two-year commissioning course, for which he has fond memories. It was, he said, a ‘military boarding school’ where the cadets had a well-rounded education, based on military training, war studies, and sport, and much of the Academy was actually ‘run by the senior and junior under-officers’.

At the end of his time as Regimental Sergeant Major of the 2nd Battalion, Ray Huggins was offered a commission. Rather surprisingly, judging from the reactions of those around him, he turned it down. He recalls receiving the ‘biggest bollocking’ since to turn down a commission ‘had never happened before’.The Regimental Lieutenant Colonel asked to see him alone, but he held his ground; the thought of a short service commission did not appeal. ‘Tell me what you do want to do?’ Ray Huggins asked to be posted back to Sandhurst as the Academy Sergeant Major, to which the Regimental Lieutenant Colonel replied, ‘I was going to offer you a regular commission’. However, Ray Huggins had made up his mind, and fortunately for the many members of staff and 5,471 cadets that passed through the gates of Sandhurst during his tenure, it was there that he was to spend the next 10 years. And as Ray Huggins reflected all these years later: ‘Had I accepted that commission, who would have remembered me now?’ It is clearly a decision he does not regret.

Ray Huggins enjoyed his time at Sandhurst, and he left his mark on the place. He helped to steer the Academy though the difficult merging with Mons, and he set a high standard for all, on the drill square and elsewhere. He also had a sense of humour, something that he has retained to this day; he understands the serious side of soldiering, but also the fun and the humour.

He recalled the decision, sometime after the merging of Sandhurst and Mons, to introduce a regimental recruiting room, into which regiments and corps were encouraged to place information and posters. Both he and the Adjutant were ‘blown for’ one day by a clearly distressed Commandant - in the recruiting room. Ray Huggins waved his hand to me as he described the place ‘it was wall to wall …. Gunners, Sappers, Cavalry, and Infantry...’ But then there was a gaping blank space where the Household Division recruiting literature should have been displayed. ‘Where is your recruiting information?’, the Commandant asked. The two Guardsmen (both Grenadiers) looked at each other, and there was really only one answer for all those other worthy parts of the Army: ‘If you weren’t at Waterloo, don’t bother!’

I asked Ray Huggins about the Guardsmen who had made an impact on him during his long service. His first platoon commander, Lord Erskine, is certainly high on the list, and was someone that he often spoke about to officer cadets when he talked to them before their commissioning. He admired Lord Erskine enormously, a wartime soldier, his turnout was always immaculate, he interviewed each of his Guardsman, individually, carefully recording his notes in his leather-bound book and writing personal letters to their parents with a gold-nibbed fountain pen. He was an officer and a gentleman who had all qualities that Ray Huggins wished his officer cadets to emulate.

Arthur Spratley (‘Sir Arthur’) was another Grenadier admired by Ray Huggins. A young Drummer before the war, while on duty at Windsor Castle, he was despatched to cut some laurel leaves for the wreaths (as Ray Huggins says, ‘it was before the days of plastic’). ‘What are you doing?’ said a gentleman wearing a bearskin and plain clothes. It turned out to be The King, who then proceeded to cut the leaves for Arthur. Of course, no one believed him until a phone call established the truth of Arthur’s story. He went on to be awarded a Military Medal and Croix de Guerre, and retired as a Lieutenant Colonel (QM), later becoming a Military Knight of Windsor.

In Pensioner Mr Ray Huggins MBE. Andrew Festing

In Pensioner Mr Ray Huggins MBE. Andrew Festing |

I asked Ray Huggins what it was about these Guardsmen that he admired? They were ‘combat soldiers’, and he was clear that this was real combat rather than the post-colonial operations of a later era. He recalled his In-Pensioner friend and fellow Grenadier, Norman Mitchell, who had fought on the Mareth Line and again at Cassino. It was always the same story said Ray Huggins. ‘The position is lightly held’. His head nodded dismissively - positions were never ‘lightly held’ and it was Guardsmen of the calibre of Norman Mitchell who had to do the hard fighting; these were the men who stood out and inspired Ray Huggins.

Following a long and successful career of over 34 years, Ray Huggins retired from the Army in 1980, to become the Deputy Administrator at Blenheim Palace, a role for which he was ideally suited. He worked there for 13 years, while his wife, Sheila, was the Blenheim Gardens’ Secretary. Ray later became a toastmaster, and they both retired to a cottage on the Blenheim Estate. Sadly, Sheila died on New Year’s Eve, 2010; they had been married for nearly 60 years.

The decision to apply to enter the Royal Hospital was an easy one for Ray Huggins; he discussed it with his family and they supported his wish. It is a good place to be and there is a great comraderie here. Ray Huggins chuckled when I admired all the recent work and upgrading of facilities at the Royal Hospital. ‘Of course, they do too much for us here, it’s luxury’, he said; but who could deny that it is well-deserved?

‘You will stay for lunch?’ I was honoured to be asked, and of course it was an opportunity to continue our delightful conversation. Once we sat down in the impressive dining room, lined with the names and battle honours of the Regiments and Corps of the British Army, two small bottles appeared from a bag that Ray Huggins had been carrying.‘Would you like some red wine?’

It had been an immensely enjoyable two and a half hours, and a great privilege for me to spend time with such a distinguished Guardsman, a fine soldier, immensely proud of his family, and a ‘people person’ in all respects. I finally asked Mr Huggins to sum up his Army career, which he did with remarkable brevity: ‘90% fun and 10% character-building’. I had of course heard him say this before, a long time ago. It is a special gift, to say wise things that others do remember.

We said farewell at the grand entrance to the Royal Hospital, as I cheekily asked Mr Huggins how he normally spent his afternoons. Back came the answer instantly: ‘I am studying for an Open University degree in …. Egyptian PT’! |

|