|

‘AN UNEXPECTED FRIENDSHIP’

DISCOVERING A NEIGHBOUR WITH A REMARKABLE STORY

by Paul de Zulueta

formerly Welsh Guards

|

3rd January 1945 was the luckiest day of Alfred Khas’s life. At around 1pm that day, Alfred, an 18 year old panzergrenadier in the Waffen SS, was part of a regimental attack on the village of Szar, north west of Budapest. His regiment, along with the rest of IV SS Panzer Corps, was determined to break the encirclement of Budapest by the Red Army and save what was left of the Germans trapped in the city. As Alfred broke cover from a maize field, a salvo of Katyusha rockets, Stalin’s organs, fell close to where he was running. Concussed, with severe shrapnel wounds to his neck, shoulder, buttocks and legs, Alfred lay on the frozen earth, his life ebbing away.

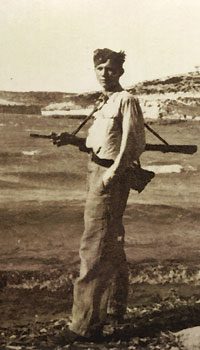

Alfred with an MG 42 on the Eastern front

Alfred with an MG 42 on the Eastern front |

Chance and fate are fickle companions to us all, and no more so than during wartime. Alfred, as he lay there numb with cold, and with Red Army soldiers just 50 yards away, could not have expected to live. But he did survive, and 20 months later found himself bringing in the harvest on an Oxfordshire farm.

I first got to know Alfred when we moved to the Chilterns in January 2007. He and his wife, Joan, lived in a small, red brick and flint cottage at the top of our lane. We struck up a neighbourly friendship but it was only when Joan died, aged 93, in February 2015 that I found myself dropping in rather more frequently to see how he was getting on. Alfred had always told me that he had served in the Luftwaffe during the war. This was true, but there was something about Alfred’s bearing, the way he conducted himself, his steadfast gaze, even his garden shed - a place for everything and everything in its place - that made me wonder about the war he had fought.

Men who have experienced visceral combat tend to keep their own counsel but as Alfred approached his 90th year, and with Joan’s health declining and her memory failing, he seemed content to unburden himself and tell me his remarkable story. Alfred was caught up in Hitler’s murderous lunacy almost from birth. He was born in 1926 in the Sudetenland, peopled by ethnic Germans, but then part of the new country of Czechoslovakia following the break-up of Austria-Hungary after the Great War. The Sudeten Crisis, triggered by Hitler in 1938, precipitated the invasion of Czechoslovakia in March 1939.

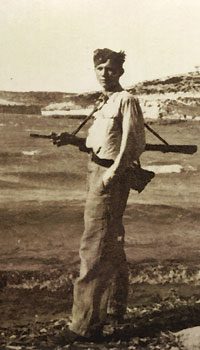

Alfred carrying a Schmeisser as he went swimming near Marseille on leave

Alfred carrying a Schmeisser as he went swimming near Marseille on leave |

His father, a builder by trade, endured harsh times after the ruinous Treaty of Versailles and was later to die in 1946 as a refugee when the Iron Curtain came down. Alfred was serving his apprenticeship as a mechanic when the German Sixth Army died at Stalingrad in February 1943. He knew then that it was only a matter of time before the bell sounded for him and, in October that year, he joined the Luftwaffe. His was a calm baptism, serving initially as a runway repairman in Carcassone in France, before serving as an air defence gunner near Vienna. There is a photograph of Alfred about to go swimming off the coast of Marseille in the late spring of 1944, his playful and youthful appearance an unknown witness to the horrors he was about to face.

By August 1944, the German army had bled white. The Waffen SS, ‘The Fuhrer’s Firemen’ had lost 35 percent of its strength, killed or missing in action. In the same month, Alfred said farewell to any glimmer of youthful innocence that he had held onto, and was conscripted to the Sixth Panzer Regiment ‘Theodor Eicke’ of the 3rd SS Panzer Division Totenkopf. As he embarked on the troop train to Warsaw, Alfred remembered looking around the carriage at his fellow ‘volunteers’, their faces a mixture of bewilderment and bravado. On reaching the railhead at Modlin, northwest of Warsaw, they spent their first night in a wood, a night Alfred would never to forget.

Russian artillery had pinpointed their position. He remembered frantically digging a foxhole as he first experienced the devastating impact and the howling sound of the Katyusha rockets. By morning, he was just one of two survivors from his section of nine men.

For the next three months, Alfred’s division, the SS Totenkopf, and two other divisions in the IV SS Panzer Corps held the Vistula line and destroyed the Soviet Third Army. His was a grim routine: two hours ‘on’ manning the MG42, a machine gun with a ferocious rate of fire and a sound like tearing cloth, and four ‘off’ though he remembers the reverse as being closer to the truth; no relief, change of underwear or clothing until Christmas 1944; the ration truck arriving every night with heavily fatted goulash, which then took back the bodies of his comrades killed by snipers or caught by Russian artillery; the resilience of the SS artillery and panzer regiments who helped crush wave after wave of Russian tank attacks; the blood curdling cries of ‘huzzah’ as Russian infantry charged their position, the Red Army artillery firing behind, as well as in front of their infantry, to ensure there was no retreat; and his worst and abiding memory of the weekly task of manning the ‘Horchposten’, or listening hole from last to first light, as Russian soldiers crept up to within 50 yards to cut the barbed wire.

Alfred caught my look of astonishment as I listened to his story, and smiled wistfully. “Well, what else could we do,” he said. “We were all in the same boat, I had a parcel from mother once a week with biscuits, cake and fruit, a Fuhrer paket (a parcel from Hitler) and a ‘Front Kampfen Paket’ (frontline parcel) with chocolate and cigarettes once a month. I was 18. You can put up with a lot at that age. I am telling you this now after 70 years, but really it was just horrible.” Alfred then looked away, stood up and walked to his garden.

In Christmas 1944, Alfred was finally taken out of the front line. He remembered going back to a house with a large ground floor room with a stone floor on which were placed red hot stones. It served as a sauna, the filth and lice of three months falling off him like dirt from a shovel. He was given his first set of clean underwear and a ‘new’ uniform sown with patches of new cloth which he sensed had once belonged to a soldier killed in action. Forty eight hours later and the ‘Fuhrer’s firemen’ were on the move again, this time to rescue the occupants ‘Trapped in the House’, the IX SS Mountain Corps encircled in Budapest by the Soviet 7th Guards Army. Once again, Soviet intelligence had the measure of German troop deployments. As Alfred deployed to the German front line at Tata, north west of Budapest, on New Year’s Eve 1944/5, the Red Army gave the German troops a rousing New Year with loudspeakers playing ‘Lili Marlene’ accompanied by a ferocious barrage of artillery and Katyusha rockets.

At first light on 3rd January, Alfred, along with the rest of IV SS Panzer Corps, began the assault on Budapest known as Operation Konrad 1.

And so began the luckiest day of Alfred’s life. As last light approached that day, three of Alfred’s comrades who saw him fall came back to pick him up, not knowing whether he was alive or dead. Taken back to a small village, a Hungarian woman gave him a glass of milk as an SS doctor took one look at him and said the four most important words that Alfred was ever to hear in his life: ‘Ya, einen heim schuss’ (Yes, a home run). Patched up in the Division’s field hospital, Alfred was put on a Red Cross train and arrived in Hamburg nine days later. The hospital in which he was to spend the next three months was, before war broke out, the Hotel Tivoli in Winsen. Alfred remembered little of his time there, just the blissful feeling that, for him, the war was over and the memory of Klaus, a badly wounded soldier in the next bed who, addicted to morphine, was then given a daily injection with nothing in it, which had exactly the same effect.

On 19th April 1945, good fortune once again blessed Alfred. The British 11th Armoured Division captured Winsen and Alfred was moved to the British Military Hospital (BMH) in Munsterlager where he continued to recover from his wounds until December 1945. I asked Alfred if he knew what had happened to his regiment in the break in to relieve Budapest. Momentarily, Alfred lost his composure, tears welling in his eyes. He told me that, by coincidence, he met a former comrade in the BMH who said that only a handful had got out alive and those that did were handed over to the Russians by the Americans at the end of the war, only to disappear into the Gulags.

Alfred’s run of good luck continued. He had no Waffen SS blood tattoo mark because he had been transferred without choice from the Luftwaffe and, unlike those who had volunteered for the Waffen SS, it also meant he was eligible for a German war pension when the time came. Still, he was considered enough of a risk not to release him in Germany when he returned to full health in early 1946, but to send him back to a POW camp in Britain.

Whatever Alfred was expecting when he arrived at the badly bombed Tilbury docks from Antwerp on 23rd April 1946, it was probably not to be offered a soft cushion seat on the train and served a mug of strong tea with milk and sugar and a cottage loaf with jam and butter. POWs with surnames A-K were sent to Henley-on-Thames and, as Alfred gazed out of the window along the Thames from Twyford to Henley, on a splendid spring day, the bluebells bursting forth in the beech woods alongside the river bank, he felt for the first time for as long as he could remember, a sense of peace and renewal.

On the first night at the POW camp at Badgemore Park just outside Henley, the Guard Commander, an Austrian Jew serving in the British Army, called the prisoners together. He apologised that the mattresses for their bunks had not arrived but would do so the next day. When Alfred told me this story, we just looked at each other, a moment of shared understanding and quiet acknowledgement.

Psychologists call it ‘Soft Fascination’, the healing power of nature. Alfred and his fellow prisoners became part of the Land Army and although they would not have realised it at the time, working on the land could not have been better therapy as they sought to mend their bodies and minds. At 7am, six days a week, they would clamber on to trucks which would then drop them off where work needed to be done: cutting hedges, planting trees, cultivating crops, ploughing the fields, helping to bring in the harvest, even helping to cut the lawn for elderly people. Work finished at 4.30. They enjoyed normal army rations and fruit and vegetables often given to them by the people and farmers for whom they toiled.

As a prisoner of war in England, with the Land Girls - 1947

|

‘The Badgemore Boys’ at Badgemore prisoner of war camp near Henley-on-Thames - 1947. Alfred is second left with fellow prisoners of war, Sepp, Willi, Kurt, Jurgen and Helmut, all of whom had served in SS Totenkopf, SS Das Reich or SS Hitler Jugend. Well fed, gramophone, pets. Quite a contrast to those of their comrades who ended up in the Gulags |

On 2nd November 1949, Alfred was released and returned to his native Germany. But his homeland was still in a desperate state and, in late November he returned to Henley and the Chiltern Hills where he had found solace and a measure of peace denied to him for so long. Many others did the same, content to rebuild their lives in an England, tolerant and as Churchill had asked, ‘ Magnanimous in Victory’. It also helped that Clement Atlee, an outstanding Labour prime minister, had the foresight to ensure every POW was issued with a return ticket. Britain needed the labour.

They say you can tell a lot about a man by the way he dances. In December 1949, Alfred, who was now working for a Mrs Hancock at Bix Manor outside Henley met his future wife Joan, at a dance in the village Hall at Russell’s Water. Alfred knew how to waltz, a dance for couples which, in its purest form, never breaks the embrace between the two, and which originally came from Bohemia, Alfred’s home region. Barely five years after the war had ended, it could not have been easy for Joan, an attractive, practical woman who saw the best in everyone and whose father had died from the effects of German mustard gas in the First World War, to begin a relationship with a former German POW. But such was the elegance of Alfred’s waltzing, his innate courtesy and kindness, and the absence of any ill will from Joan’s friends and family, that they felt able to marry on St Patrick’s Day, 1951.

With reconciliation comes rebirth, and other POWs, Kurt, Willi and Sepp who chose to remain in England followed Alfred and Joan’s example. They became the nucleus of the Anglo German club in Oxford which, by the early 1960s, boasted 240 members. Dancing, particularly the waltz, became the heart of their monthly get together. “No event ever produced so great a sensation in English society as the introduction of the waltz in 1813” wrote the diarist Thomas Raikes, and so it was 150 years later in Oxfordshire.

Alfred Khas, photographed in his garden

Alfred Khas, photographed in his garden

Henley-on-Thames - 2015 |

Alfred and Joan led a happy, contented life together for close to 65 years. There were times in the uncertain hours before the morning when Alfred would awake screaming as the horrors of the Eastern Front returned to haunt him. But they receded as the years passed by in the pretty small brick and flint house overlooking the Vale of Oxford where they lived for all their time together, and where they brought up a daughter, Helen. For 40 years, Alfred worked as a machinist for Broom & Wade in High Wycombe. When he retired on 8th March 1991, his 65th birthday, the managing director presented him with a pair of field binoculars, a £100 cheque and gold bracelet for Joan. As they toasted Alfred’s retirement with a glass or two of Schnapps, the managing director remarked that Alfred had never, in 40 years, taken a day off for sickness nor had once been late for work. Alfred buried Joan on a warm and bright early spring day. Drifts of wild daffodils framed the path to the entrance of St Botolph’s Church in Swyncombe, close to the ancient Icknield Way. Though Joan was 93, there must have been fifty people present. Only one of Alfred’s fellow POWs was still alive and present: Sepp, not easy to miss, 91 years, close cropped steel hair, still the bearing of a German Fallschirmjäger who had fought in the Battle of Crete in 1941.

A day or so later, I went to see Alfred at his house. He was shaky on his feet and understandably a little lost. I said it had been a good funeral and that I was glad so many people had come to say goodbye to Joan, and that clearly she had been much loved. For some reason I added, ‘You know Alfred, 70 years ago, you were lying on a frozen field on the Eastern Front left for dead. You’ve had a wonderful life since then, a lot to be thankful for. Instantly, Alfred braced up, looked me in the eye and simply said ‘Yes.’ A week later I saw Alfred tending the roses in his garden, finding once again the solace and comfort of working with nature that had so helped him to recover as a POW. As I walked home later, I found myself thankful for what had become an unexpected and rewarding friendship. Alfred, a good man caught up in Hitler’s madness, had found peace and self worth in a country against whom he had fought a brutal war. His story of reconciliation and renewal, buried for 70 years, had also made me proud to be British. |

|