|

DAVID SMILEY IN OMAN

by Major J R Fitzgerald

The Blues and Royals

|

The sinner who goes to Muscat has a foretaste of what is coming to him in the other world

Persian proverb

The British relationship with Oman until the mid-20th century was characterised by imperial interests in India, and at best could be described as quiet. Not until the prospect of the discovery of significant oil reserves and the granting of a concession for the whole of Muscat and Oman to a predominantly British oil company did British support for the Sultan solidify. It was hoped that Omani oil could provide a much-needed lifeline to the flagging post-war British economy and that stronger Anglo-Omani relations could help to stall the erosion of British presence in the Middle East, increasingly challenged by Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United States.

But the situation was far from simple. The territory now known as Oman was then divided between the (interior) Imamate of Oman and the (coastal) Sultanate of Muscat; ambiguous national boundaries fueled the territorial machinations of neighbouring Saudi Arabia; and tribal loyalties, on the promise of Marie Theresa Thalers, could shift almost as fluidly as the sands on which they lived.

Following a successful British-backed campaign against the Imamate in 1956, well-documented in Jan Morris’s Sultan in Oman (Said bin Taimur, the Sultan of Muscat), the Imam was routed, and his territories seized, seemingly for good. But in 1957, the Imam, again funded by the Saudis, re-emerged, targeting the Sultan’s troops and the national oil company from his Jebel Akhdar stronghold. So, it was in 1958 that the miserly Sultan again turned to the treaty-bound but reluctant British for help.

‘You must know, Colonel Smiley, that all revolutions in the Arab world are led by colonels. That is why I employ you. I am having no Arab colonels in my army’, Sultan Said in 1958

Born in 1916 and commissioned into the Royal Horse Guards in 1936, by the time he was approached in 1958 by Julian Amery, the Under Secretary for War, with whom he had served on special operations in Yugoslavia during the Second World War, David de Crespigny Smiley had served with the Somaliland Camel Corps, raised the siege of Habbaniya in Iraq under ‘Glubb Pasha’, captured Tehran, parachuted in to Albania for SOE (MC and Bar), been blown up in Siam, taken the surrender of Laos from the Japanese (OBE), ridden alongside The Queen as Escort Commander at the Coronation, been the Defence Attaché to Sweden, and achieved the record for the most falls in one season on the Cresta Run.

Amery was suitably persuasive, and Smiley put his retirement plans on hold to accept the command of the then Sultan of Muscat and Oman’s Armed Forces (SAF).

Sultan Said bin Taimur

Sultan Said bin Taimur

and Colonel David Smiley |

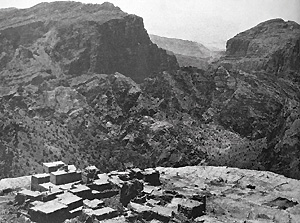

Jebel Akhdar, 3,000m above sea level

Jebel Akhdar, 3,000m above sea level |

When Smiley arrived in 1958, the Sultan personally tasked him with dislodging the Imam’s forces from the Jebel Akhdar area and building up the SAF. He lost no time in conducting extensive reconnaissance and dispatching fighting patrols and Royal Air Force sorties that fixed the rebels on Jebel Akhdar, an area larger than Cyprus.

Smiley’s request for reinforcements of a brigade with two battalions from the Marines or Parachute Regiment was rejected in London by Ministers who were sensitive to Egyptian, Saudi, and Soviet condemnations of ‘British imperialism’. Instead, Smiley was handed a deadline of April 1959 for the withdrawal of all British troops from Muscat.

Following a series of diversionary attacks and a disinformation campaign, on 25th January 1959 Smiley launched, against the Imam’s forces, a combined force of SAF, Trucial Oman Scouts, D Squadron, The Life Guards (on loan from Aden), A and D Squadrons, 22 Special Air Service (on their way back from Malaya), and some specially imported Somali pack-donkeys. 1000 years earlier, the Persians had won a bloody battle on Jebel Akhdar by carving steps in to the rock, and up these same steps the SAS began their assault. False reports spread by the loose lips of the donkey drivers deceived the Imam’s men into reinforcing the wrong positions, and the SAS made quick work of the resistance they faced, although sadly two soldiers were killed when a chance bullet exploded a grenade in a day sack. Mistaking the supply drop for parachutists, the remaining enemy panicked and melted away. The Life Guards had man-packed the Besa machine-guns from their Ferret armoured cars up the same arduous route to secure the heights that the SAS had captured.

The collapse of enemy resistance came as a welcome surprise and, with it, for the first time, the villages of the Jebel were brought under the Sultan’s direct control. Many of those involved in the operation believed Smiley should have been awarded a DSO. The British press rightly lauded the efforts of the SAS but to Smiley’s chagrin, The Life Guards were barely mentioned and the SAF were totally ignored. In the resulting years he fought tooth and claw to get a campaign medal awarded for all those who participated but was refused by the War Office, though it eventually conceded the ‘Arabian Peninsula’ clasp to the General Service medal, the same distinction shared with ‘every desk-bound clerk in Aden or Bahrain’.

Down but not out, the Imam did not capitulate. Six months later, his rebels recommenced low-intensity activities, predominantly mining roads. However, deprived of their mountain refuge and pressured by Smiley’s creation of a gendarmerie, tracker training, imposition of fines for mine layers’ villages, development projects and an effective intelligence network, the embers of the Imamate were eventually extinguished.

Colonel David Smiley, Commander,

Colonel David Smiley, Commander,

the Sultanís Armed Forces |

The Household Cavalry Regiment on Exercise SAIF SAREEA 3

The Household Cavalry Regiment on Exercise SAIF SAREEA 3

in Oman, October 2018 |

Now Smiley could turn to his principal task: building up the strength of the SAF. From 1959-61 he expanded the SAF from 800 to 2,000, a difficult task in light of the Sultan’s insistence on maintaining the balance of 70% Baluch to 30% Arab. The Sultan had little trust in his fellow Arabs and favoured the occasionally mutinous Baluch, who ‘whether from courage or simple inability to appreciate danger… would hold his ground even under heavy fire or determined assault’. The officers were all British, either on contract or secondment. By the end of Smiley’s three-year contract, the SAF’s standing had been significantly improved, with Smiley leaving ‘happy to think I should never see Arabia again’.

David Smiley left Oman in 1961, declining the offer to command the SAS, and instead chose to retire, filing occasional reports for the Good Food Guide. But he did not last long ‘eating more bad meals than good’. In 1963 he performed a characteristically unorthodox volte face - gamekeeper turned poacher - joining the Royalists in Yemen in their bid to restore the Imamate overthrown by the Nasser-backed government (see Duff Hart-Davis’ The War That Never Was) and writing for the Household Brigade Magazine. Unsurprisingly in a region scarred by internecine strife and war, with the current conflict in Yemen now in its ninth year, there are similar dynamics as there were 60 years ago. The irony that his new employers, the Saudis, had been funding the insurgency in Oman, was not lost on Smiley and demonstrates the complexity of Middle Eastern politics.

Without the successful conclusion to the Jebel Akhdar rebellion, the Sultan would not have been able to concentrate his resources on the emerging Soviet-sponsored insurrection in the Dhofar. At the same time, it enabled the Sultan to begin on the ‘hold’ and ‘build’ phases of the counter-insurgency in the Imam’s heartland. The bar was low, but liberated from the threat of the Imam, Sultan Said set the foundations for the state that Qaboos would solidify, catapulting Oman into modernity.

Sultan Said was overthrown in an (almost) bloodless coup by his Sandhurst trained son, Qaboos, in 1970 and banished to the Dorchester Hotel, where he remained for the last two years of his life.

The caves that sheltered the Imam’s men on Jebel Akhdar remain, while most guests to the mountains now choose to stay in one of the five-star hotels where they can enjoy the dramatic topography with its fabled impregnability that was to be disproved by the SAS’s defiant night climb. Perhaps this is why access to the mountain on top of which sit two SAF barracks and a police station is still closely monitored by a military checkpoint, a reminder that history is not forgotten readily here.

Much of David Smiley’s Oman is now unrecognizable. Slavery has been outlawed; sunglasses are legalized, and schools, hospitals and roads abound. Yet the hallmarks of British influence and Smiley’s contribution remain imprinted on the Sultanate. The SAF are advised by the Loan Service, led by Major General Richard Stanford WG, and many of its Omani officers are graduates of Dartmouth, Sandhurst and Cranwell. Exercise SAIF SAREEA, in the autumn of 2018, in which David Smiley’s regiment participated, demonstrated the depth and development of Anglo-Omani military relations, something that would have been inconceivable in 1961.

It was in 2009 as an Arabic student that I first read about Colonel David Smiley, though sadly it was through his newspaper obituary. A former Commanding Officer of the Royal Horse Guards, his sword hangs on display in the Full-Dress Store in Hyde Park Barracks, a reminder of the adventures awaiting beyond State Ceremonial and Public Duties.

For further reading, see: Clive Jones’s review of The Clandestine Lives of Colonel David Smiley (The Guards Magazine, Winter 2019/20), and 50 Years Ago: From the Household Brigade Magazine, Spring 1968, republished in The Guards Magazine, Summer 2018: A Walk in the Yemen by Colonel D De C Smiley LVO OBE MC and Bar. |

|