|

Major General P G Williams CMG OBE

formerly Coldstream Guards

In conversation with The Editor

|

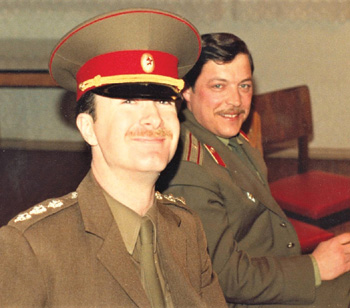

With the Battalion Intelligence Section in West Belfast in early 1976 With the Battalion Intelligence Section in West Belfast in early 1976 |

I first met Major General Peter Williams, properly, in the fifth-floor café of Peter Jones on an afternoon in the late summer of 2013, surrounded by shoppers, young mothers, children, prams, and shopping bags!

This was hardly a formal interview since there was a non-existent list of candidates to succeed Peter in his role as Editor of The Guards Magazine; it seemed that I was the only candidate! Peter had been Editor since taking over from Oliver Lindsay in late 2008 and was now preparing the way to hand over to his successor. Over a cup of tea, we discussed the various challenges and occasional frustrations of being an editor and having expressed my enthusiasm for taking on the mantle, Peter indicated that he would recommend my name to the Major General. I was extremely grateful.

What follows below is really no more of an interview than my meeting with Peter in 2013! A while ago I asked Peter if he would be happy to have a conversation with the Editor along the lines of previous interviews published in The Guards Magazine. His natural modesty prompted an initially quizzical response (‘An interview about what?’), but a few days later, in response to some written questions, Peter drafted the interview for me! Editorial habits die hard, and I am certainly not going to start playing with the words of my distinguished predecessor!

As a preamble to our ‘virtual’ conversation for this Autumn edition of the magazine, some background on Peter’s Army career. He joined the Coldstream in 1972, having been educated at Eton and Magdalene College, Cambridge where he read History. During his 33-year military career he saw service with Coldstream battalions in Berlin, Northern Ireland, Hong Kong, Münster and Bosnia, as well as London. Most of his time was spent in extra-regimental posts: in a Baluchi battalion in Oman in the mid-1970s; twice in East Germany with BRIXMIS in the 1980s; two further tours in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s; two postings to SHAPE, including as the MA/Speechwriter for SACEUR; serving on the EU Military Committee; and finally as the Head of the NATO Military Liaison Mission in Moscow until 2005 during the brief period of rapprochement with Putin’s Russia. At the end of his time in Moscow he became the first serving member of the Household Division in over half a century to be made a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George.

And here are Peter’s answers to my questions.

Why did you join the Army and why did you choose the Coldstream?

I was brought up in a military family; both my father and my elder brother were in the Light Infantry. I wanted to join something different and my schoolfriend, Richard Boggis-Rolfe, suggested that I try for his regiment, the Coldstream. My interview with the Regimental Lieutenant Colonel, Timmy Smyth-Osbourne, was an unforgettable introduction: ‘Do you play polo?’ ‘No, Sir’. ‘But you do ride, don’t you?’ ‘No, Sir, but I could learn’, as I began to question whether this was indeed the Foot Guards. ‘I used to hunt with your father in Cornwall before the war, didn’t I?’ ‘Yes, Sir’. ‘Well, that will be fine’. With which I became a Coldstreamer!

What do you recall about your officer training?

Sandhurst was an interesting experience because ours was a 36-strong all graduate intake in Victory College. We arrived on Direct Entry Course No 1 as Second Lieutenants in our respective regimental and corps uniforms and, as such, we were the despair of our long-suffering instructors throughout our six months at the Academy.

My time on the Platoon Commanders’ Course at Warminster was altogether more memorable, not least because three of us in front of the Bombard OP at Larkhill were almost killed by an inert Chieftain TPTP round that we saw coming towards us before it buried itself deep in the chalk only ten yards away.

I also had a close shave in a live ‘tank grenade stalk’ battle handling exercise when the plastic explosive charge on the target tank almost lifted the turret off the hull and showered us, barely twenty yards away, with steel ball bearings and hatches. Our SASC instructor apologised for having ‘over-egged the plastic’ and swore us to secrecy about his near-fatal mistake.

Who in the Guards had a particularly positive impact on you?

Within nine months of reaching the 1st Battalion in Berlin I had been made the Intelligence Officer, a job that seemed to be reserved for ‘smart alick’ graduates. Faced by all the excitements offered by Flag Tours in East Berlin, as an observer on the British Military Train and later in West Belfast, I needed a steadying hand on my shoulder and this was provided by the then CSM, John Rigby. He was a fount of wise advice and taught me that patience and empathy were key attributes of a good Coldstreamer. John may be gone, but he most certainly is not forgotten.

What were the highlights of your time as a Coldstreamer?

I spent more than half of my career abroad, much of the time in extra-regimental posts. In Oman I was fortunate to serve in the Frontier Force in Dhofar just after the war had ended, first as the Operations/Intelligence officer and then as a company commander. There my Commanding Officer was Jonathan Salusbury-Trelawny, who was not only a fellow Coldstreamer, but also a cousin. He allowed all of his British officers to operate on the jebel on a loose rein, using their initiative and learning from whatever went less than perfectly. It was an unforgettable experience for a young officer.

Having learned Russian and some German at the Army School of Languages in Beaconsfield, in the 1980s, I went on to serve twice in BRIXMIS, the British military liaison mission to the Soviet Army in East Germany. Once again it was a joy to work for Chiefs (brigadiers) who were prepared to allow their unarmed officers and non-commissioned officers to operate out on the ground with only the lightest of restraints. As far as our Chiefs were concerned, the only impermissible intelligence collection activities were ones that might imperil the long-term existence of the Mission.

The Fall of the Berlin Wall initially suggested that all the experience gained in BRIXMIS was going to be of little or no use in the ‘brave new world’ that was forecast for the 1990s. However, the rapid disintegration of Yugoslavia provided me and others with countless opportunities to practise what we had learnt about the ‘Fantasian Army’ in the 1970s and 1980s. The Yugoslav warlords with whom I interacted during my three six-month tours in Bosnia and Croatia were cut from the same dogmatic, bloody-minded, and devious cloth as their Soviet and East German allies had been.

Working for the United Nations, first commanding my Coldstream armoured infantry battlegroup in central Bosnia as part of the UN Protection Force, and then as the Deputy Chief UN Military Observer in the last months of the war in 1995, I discovered that the liaison and intelligence skills that I had honed in Belfast, Oman, and East Germany were totally applicable to the challenges that faced us in Bosnia.

Whilst it was useful to carry a big stick in the form of a Warrior-equipped battalion, any measure of success had to be founded on consent on the part of the warring factions and winning that consent was a constant battle of wits. It was often frustrating, but when things went well and we managed to assist in getting humanitarian supplies to cut-off communities and to convey the truth to the international media, it was the greatest of fun.

Several years after NATO’s Stabilisation Force had taken over responsibility for security in Bosnia from the often unfairly under-rated UNPROFOR, I went to serve in HQ SFOR as its Chief Faction Liaison Officer. By that stage many of the old Bosnian warlords were either on trial for war crimes in The Hague or were being pursued by Allied special forces. Most of the other wartime leaders had become ministers and senior commanders and they welcomed me back because I represented an all-too-rare sense of continuity on the part of the NATO occupying authorities. Once again it was great to be practising ‘creative liaison’, but it was never going to be as much fun as it had been during what one Bosnian Croat general described rather dubiously to me as ‘the romantic days of the war’.

After a brief interlude as the first British representative on the European Union Military Committee which was, frankly, a rather surreal experience, I found myself as the unexpected beneficiary of Tony Blair’s patronage.

Apparently, the then NATO Secretary General, Lord Robertson, had mentioned to the Prime Minister that the Alliance was finally planning to open a military mission in Moscow and Tony Blair had magnanimously responded that Britain would, of course, provide the first Head of the NATO Military Liaison Mission. As a result, I was extracted from Brussels and sent at short notice to Moscow just in time to see the Mission open in late May 2002.

After a quarter of a century viewing the Soviets and then the Russians as the main threat to peace and having enjoyed numerous postings where I had seen the concept of ‘liaison’ being interpreted very flexibly and at times being used almost as a synonym for ‘intelligence collection’, heading up the NATO MLM was to prove to be a completely new experience. Policy and programmes were decided by the NATO-Russia Council in Brussels and our job was to help the Russian Ministry of Defence to deliver whatever the politicians had approved. As a job it had its fair share of frustrations, but as a family posting it was peerless. Moscow is one of the world’s great cities and it was a real privilege to spend three years getting to know it.

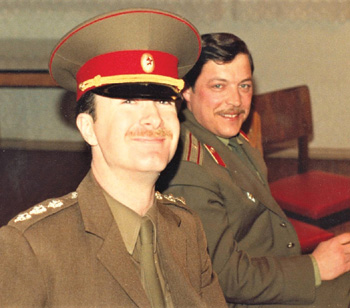

Liaising with the Soviets in Potsdam in 1982

Liaising with the Soviets in Potsdam in 1982 |

As Head of the NATO Military Liaison Mission in Moscow, 2003

As Head of the NATO Military Liaison Mission in Moscow, 2003 |

What were the experiences that frightened you most?

One particular event, a helicopter ‘crash’ in Dhofar in 1977, comes to mind when I think about frightening experiences. I was a passenger squashed in with numerous Baluchi soldiers and a goat in the back of a Huey helicopter that was being flown by an experienced ex-Royal Marine pilot.

He had launched the over-laden aircraft off the very high coastal scarp, expecting the ‘stall klaxon’ to stop squawking and the main rotor to increase its lift as the helicopter dropped towards the sea. However, just as the ‘stall klaxon’ ceased and the rotor started to respond to the thicker air, there was an appalling sound of something breaking. The aircraft lurched violently and started to spin; trapped in the cabin I could only assume that the tail rotor had broken off. The pilot fought to gain control and to establish where the horizon had gone.

Being briefed by the Russian military in 2005

Being briefed by the Russian military in 2005 |

After ten or so fraught seconds, the pilot regained control and we started to fly forwards … at which point the passenger in the co-pilot’s seat jettisoned his door! In the event we landed safely at a coastal village and the damage became clear: the Plexiglass panel above the pilot’s head had imploded with great force and for no obvious reason, severely disorienting, but fortunately not injuring him. We were saved by his instinctive reactions, but it did make me appreciate how narrow the line is between good fortune and disaster.

Why did you leave the Army in 2005?

I left the Army at the end of 2005 when the Military Secretary decided that he had no further use for me. Some people seem to ease seamlessly into a new life and a new career. I found the transition very difficult, just as my brother, who had been Director of Tri-Service Resettlement, had warned me would be the case: ‘Many admirals, generals and brigadiers find it hard to settle in part because civilians have no idea about what they have been doing and they assume that because we have little commercial experience, we have no translatable experience to offer’. And so it proved to be.

Eventually I decided to devote my efforts to things that I wanted to do, rather than spend more anxious months chasing elusive jobs. I enjoyed five years as the Editor of The Guards Magazine and have kept busy since handing on the baton to my interviewer.

What has the Army taught you about life?

As a small boy I always wanted to be a soldier and I loved almost every day of my life in the Army. Looking back, I was fortunate enough, partly by good luck and partly by intention, to follow a career path that involved intelligence, liaison, and languages and that was focused on dealing with people whose culture and aims were often very different from my own. It is not for me to judge, but I like to think that the Coldstream knocked me into shape and that I have emerged as a more rounded and empathetic individual than the young man who entered Victory College back in late 1972.

Reading Peter’s answers to my questions, it seems to me that his career encapsulates so many of the events that defined the period from the early 1970s to 2005, when he retired from the Army. The Cold War is centre-stage in the first 20 years of Peter’s career, and some of the fall-out from the end of the Cold War, not least in Bosnia, has played into the closing years of his active service. Along the way, his experiences at the physically sharper end of soldiering, notably in Oman and Northern Ireland, have ensured that his core-skills as an infantryman have never left him. His summing up of his career path as involving: ‘intelligence, liaison and languages’ are qualities that the Army will certainly need plenty of in the years to come.

Peter continued in his role on the Editorial Committee as Regimental Representative for the Coldstream Guards since handing-over the editorship of the magazine in 2013. Over this period he has written numerous articles, book reviews, obituaries, and short topical pieces. And he has occasionally ‘fired-off’ Letters to the Editor, often reminding me that ‘Mr Grumpy’ from Wiltshire can invariably be talked out of wanting to see his letter in print! Thankfully, they generally have found themselves into the magazine, although Peter has now drawn stumps on the subject of ‘berets’!

One of the most important, but inevitably tiresome, tasks of an editor is to proof-read other people’s copy and, as Peter warned me back in 2013, there are occasions when articles do need some quite extensive editing as well. Proof-reading is never easy, and Peter’s proof-reading skills will be a very hard act to follow. Never one for just a cursory and quick look through the 120 pages of the proof, Peter clearly reads everything, and not just spelling mistakes. Now that he has retired from the committee I will greatly miss his presence at our meetings, and also his proofreading skills. Thankfully, however, I know that he will continue to submit and suggest articles. And, I hope, Letters to the Editor!

Peter has provided me with much good counsel since 2013, not least the simple cry ‘You are only as good as your last edition!’ I will try and emulate Peter’s record on that score and take the opportunity here to thank him for all that he has done for the magazine over many years.

|

|

With the Battalion Intelligence Section in West Belfast in early 1976

With the Battalion Intelligence Section in West Belfast in early 1976