Home | About Us | Subscribe | Advertise | Other Publications | Diary | Offers | Gallery | More Features | Obituaries | Contact |

|

|

|

|||||||||

Readers will recall the beginning of an archaeological project at Waterloo last year that sought to use archaeological research as a vehicle to assist with the recovery of wounded, sick and injured service personnel and veterans. We had a very successful first season, and, with the generous support of individual donors and organisations, have been able to continue in 2016 and formally to establish the project as a charity. Waterloo Uncovered began with a pub discussion between two Coldstreamers, both of whom had ‘previous’ as archaeologists, and it came to fruition when one, Mark Evans, left the Army suffering from PTSD following a rough tour in Afghanistan. Inspired by earlier projects that saw injured soldiers participating on digs on the Defence Estate, we felt that it should be possible both to undertake original research and do something to improve the well-being of our comrades. During this summer, Waterloo Uncovered achieved full registration with the Charities Commission, and is now governed by a board of trustees led by Brigadier Greville Bibby. The charity is mandated to conduct three core activities, and employs one person, Mark Evans, to coordinate the planning and execution of these tasks: To undertake detailed archaeological investigations at Waterloo to further academic and public understanding of the events of 1815 To use the archaeological work as a vehicle to promote the recovery or provide respite for wounded, sick and injured veterans and service personnel To promote discussion, study and education, to maintain awareness both of the importance of the Waterloo Campaign and of conflict archaeology Though a UK-registered charity that derives much of our support and participation from this side of the Channel, we recognise and continue to promote the grand alliance that Wellington led to victory in 1815. Critical to the project are our Belgian and Dutch partners, and it is hoped that in the future we will have some formal involvement from the Dutch Army. Many of these soldiers have, of course, suffered life-changing injuries in the same theatres as ours.

During our first season, we achieved a balance between archaeologists, students and volunteers, and veterans / servicemen, in a team some 50 strong, and this year was planned on similar lines. Despite a heavy Coldstream influence at the top, we are a mixed band that includes veterans from all three services, and we are fortunate to enjoy support from the local Belgian community as well. Chief sandwich-maker and all-round helper again this year was the vicar of Waterloo’s Episcopalian church, whilst the Comte d’Oultremont, whose family owned Hougoumont from 1815 until 2004, made available his considerable and fascinating private archive for research. The archaeological team continues to be led by Professor Tony Pollard of the Centre for Battlefield Archaeology at the University of Glasgow, together with Dominique Bosquet, the Walloon regional government archaeologist responsible for the area. They are supported by some hugely experienced people, most of whom were taking a busman’s holiday from projects that actually pay them (Crossrail, for instance), with the staff at L-P Archaeology Ltd surveying and collating results and coordinating reports at cost or free of charge. When one understands the very tight margins of commercial archaeology, it is possible to appreciate what a generous gesture this is. The success of veteran archaeology hinges on the fact that there are many different jobs on a dig, from finds cleaning and recording, to photography, surveying, digging, report-writing and research, and we endeavour to give each participant as wide an experience as possible. Having this flexibility also allows people to find their niche in an environment that suits best their psychological needs and any physical incapacity. We have found, as elsewhere, that activities such as metal detecting or detailed excavation can be helpful for those suffering from PTSD in just the same way as other ‘meditative’ activities, like drawing and painting, golf or yoga. A wheelchair is no barrier at all to participation! An important aspect of this project, and one of the reasons it has been a success, is the mix of people. Students, veterans and professionals all bring different ideas and experiences, and throwing people into a trench together breaks down barriers quickly. We have seen firm and lasting friendships between those who might not otherwise have met, and the digs have a life beyond the field through social media and informal social gatherings. Soldiers have been as pleasantly surprised to have proved wrong their expectations of scruffy students, as were the students to find how keen, articulate and versatile our soldiers are! Some of the older veterans have also commented on how much they enjoy working with serving personnel. Not only does military ‘banter’ endure, but it allows a connection to the modern armed forces that is hard to find at veteran-only events. Archaeology is an ‘outdoor sport’ that can be physically tiring, demands teamwork and definitely requires a sense of humour!

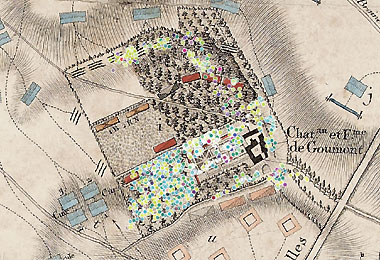

In both 2015 and 2016 we have followed a similar model, and so far have concentrated our work on the area surrounding and within Hougoumont Farm. It is important at this stage to explain exactly how archaeology can help with our understanding of a battle, and also to understand where the limits lie. Archaeology is essentially the study of human history through examination of the material remains left behind - things created, used or changed by humans. Conflict archaeology is merely the refinement of that discipline to concentrate on a singular aspect of a site - in the case of Waterloo, one day in the history of a site that has certainly been occupied by humans since the middle ages, and probably well before. Waterloo is one of the most written-about battles of all, both by eye-witnesses and historians. Nevertheless, any police officer will tell you that evidence is often unreliable. Perhaps not deliberately so, but it is a peculiarity of the human mind that when under great stress, recall of detail or understanding of time is often distorted, sometimes to a remarkable degree. Modern police investigations involve interrogating CCTV as well as witnesses, recording fingerprints and skid marks. Archaeology on a battlefield seeks to do much the same. The eyewitness accounts tell us who the protagonists were, where, how and why they fought. Most, however, can only tell us what they could see in their corner of the battlefield, through smoke, noise and violence. Historians have gone to great pains to link them together and understand the ‘big picture’, but archaeologists still have the opportunity to return to the site and see what remains. Were the buildings arranged as depicted in some of the post-battle artistic depictions? Where were the skirmish lines, and what evidence is there for fighting in the various contested sectors? Where, even, are the bodies? These are some of the questions we have sought to address in the last two seasons, and the results have been fascinating. Such is the nature of archaeology, we have uncovered almost as many new questions as answers to old ones, but it has been a wonderful journey and one that promises to continue as such. Led first by detailed map studies and analysis of historic illustrations and written accounts, in 2015 we spent much time conducting metal detector surveys in the area once wooded to the south of the farm and in the Great Orchard. These surveys produced evidence to suggest early skirmishes at the southern margin of the wood, perhaps some of the earliest shots of the battle. They revealed also the suggestion of a concentration of musket balls along a line that corresponds with a woodland ride or track shown on some maps but not others. Such a concentration, knowing that ‘tracks attract bullets’, would seem consistent with an organised withdrawal and supports written accounts. Closer in, around the notorious ‘killing ground’ to the south of the garden wall, we found impacted Brown Bess balls along the hedge line, and French balls, still bearing the marks and brick dust of strikes, along the wall footings. This 40 yard expanse was a death trap to the French, and the evidence of close-quarter fighting survives to this day. The wall itself, loopholes and all, has been rebuilt since the battle, probably more than once. That the loopholes were included in the reconstruction demonstrates the importance that Waterloo has held for tourists ever since the battle, an impression reinforced by the coins we have found in the area, from a dozen different countries and stretching through two centuries. Elsewhere, we found what we believe to be the track-bed of the ‘sunken way’, which lay, to our surprise, nearly six feet below modern ground level. Indeed, we were taken aback by the degree of re-modelling that seems to have happened to the north of the farm, much of it linked to motorway construction in the 1970s. When one starts to understand the historical profile of the ground, the sunken way becomes a great deal more significant, and so too does the restriction of sight lines to and from the farm occasioned by the wood to the south. In its modern form, stripped of cover and structurally reduced, Hougoumont offers very little defensive value at all, but in 1815 it must have been quite formidable. In 2016, we returned with several new archaeological aims, both to satisfy the Intercommunale who own the farm, and our own research. Chief amongst these was to investigate whether or not there was in fact a grave close to the south gate. Several well-known illustrations of the aftermath of the battle depict the burning or burying of bodies at this site, and it was felt, understandably, by the owners that its current use as a car park might not be appropriate if it was indeed a grave. Under the expert eye of Gaille MacKinnon of the University of Dundee, the area was excavated to more than six feet, and over a wide expanse. Gaille is one of the few dual-qualified forensic anthropologists and archaeologists in the UK, and has worked on a huge variety of sites across the world, as diverse as Balkan war graves, WW1 cemeteries, ancient burial sites, and modern police investigations. To our surprise, much of the material was found to be modern fill, with no obvious disturbance to the natural ground layer beneath, and no sign of a grave or cremation pit. Of course, one cannot rule out the existence of a pit in this area, but it certainly is not there now. There has been much remodeling of the farm over the last century, to provide hard standing for machinery and perhaps to improve drainage. Such a discovery is, of course, welcome to the owners, who do not now have to contemplate moving their car park, and we do not need to face the complexity and ethical challenges of human remains, but the question remains: ‘where are the bodies?’ Other Napoleonic battlefields, notably in Lithuania, are known to have been systematically ‘mined’ for remains to feed an agricultural bonemeal market, and though there is less evidence for this happening here, it is certainly a possibility. Equally, the remains that were interred here may have been fragmentary, semi-cremated and fewer in number than suggested by the more lurid accounts. So perhaps we have simply been misled by history? Elsewhere in the farm, another perplexing conundrum has emerged. In the garden, said by most allied accounts to have resisted all French attempts to gain access, although some French accounts claim otherwise, we have found French musket balls in reasonable numbers and bearing the unmistakable signs of having been fired. Tempting though it is to announce a great discovery, nothing is ever so simple in archaeology. In 1796 there had been a skirmish at Hougoumont, during the War of the First Coalition, in which Revolutionary France annexed territory that included what is now Belgium. We have French musket balls, but we cannot be certain when precisely they were fired! A particularly satisfying piece of work was undertaken inside the farmyard itself by Phil Harding, from Time Team, alongside his colleague Carenza Lewis. A long-standing supporter of the Defence Archaeology Group, Phil generously agreed once more to be a trench supervisor, and has been passing on his formidable skills in field archaeology. Just inside the north gate, test trenches revealed the footings of the farm buildings destroyed during the battle, including, in some areas, collapsed rubble, burnt material and roofing slates. This suggests that some of the debris of the battle may survive in situ and we intend to conduct a much wider excavation of this area next year to see what might be trapped beneath the rubble. The deepest layers survive in good order, and construction was to a good standard, as shown by the stable drain culvert and sump found by Phil’s group, so it should be possible to find and mark the exact footprint of the lost buildings in this area.

Our attention now is focused on two major tasks. One is to consolidate and publish the work so far (which we have covered in presentations in schools and elsewhere), and also to raise funding to secure the future of the project. Thanks to very generous individual donations and the support of the Coldstream Guards, the Household Division, the ABF, and a number of other charities, we have kept the show on the road so far, despite the fact that this is an expensive game even when our professionals work for free! In July we finally became a ‘proper’ charity, registered with the Charities Commission. A fairly expensive and complicated process in its own right, it is a significant milestone, allowing us to bid for longer-term funding from sources previously off-limits. We enjoy the guidance of an experienced group of trustees, and are able to plan to continue what we have started for several years to come. There is more archaeology to do at Hougoumont and we intend to return next summer to continue the work. Beyond Hougoumont, the Waterloo battlefield is a compelling and little-studied archaeological site. We would like to know, for instance, if modern survey techniques will allow archaeologists to identify, from shot scatter, the sites of individual squares, and we have been asked if we are interested in undertaking a ‘rescue’ dig before planned building work at one of the important buildings on the fringes of the battlefield. Most importantly, our wounded, injured and sick participants are doing something worthwhile, regaining confidence in their abilities, learning new skills, and meeting new people. One injured soldier, having never seen an archaeological site before being ‘voluntold’ to participate by his company commander in 2015, is now applying to study archaeology at university, and I hope he won’t be the last. On behalf of the Trustees, partners and participants in Waterloo Uncovered, I would like to thank in particular the Major General and Trustees of the Household Division Funds, the Coldstream Guards Regimental Fund, Grenadier Guards Colonel’s Fund, the Dougie Dalzell Memorial Trust and the Cavalry & Guards Club for their continuing and extremely generous support. Both moral and financial, this project would not exist without the strong encouragement and help we have received from both large organisations and individuals within our great family, together with many more from the wider Service community and outside. We are extremely proud of the fact that this is not an exclusively Household Division affair; rather, we are leading the way and bringing others with us, in the spirit of our motto: Septem Juncta in Uno. Anyone wishing to know more about Waterloo Uncovered, and who interested in following the future progress of the project, may discover more at www.waterloouncovered.com. If you would like to write or speak to Mark Evans or Charles Foinette, we can be reached via the Editor.

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||