|

THE BATTLE OF LOOS - 1915

by the Editor

|

The Battle of Loos is one of those First World War battles that seems to exemplify all the worst aspects of that terrible war. Much was expected of this offensive, ‘The Big Push’ as it was named at the time, but it was to be a costly and futile endeavour that later provided a touchstone for many of the harshest judgements of the war. The tragedy was that the Allies were still struggling to come to terms with this new kind of warfare. They had yet to grasp the basic mechanics of attacking strong fixed defences, and yet ‘attack’ seemed the only option.

|

1915 had been a bad year, with France suffering huge casualties and mounting pressure on the British to do more along the Western Front. Elsewhere, the Gallipoli campaign had foundered and the Germans were gaining on the Eastern Front. At home, Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, had resisted committing his New Armies, but now changed his mind. On 19th August, he ordered Sir John French to launch an attack at Loos in support of Marshal Joffre’s offensive. New Army divisions and the recently formed Guards Division would see action for the first time.

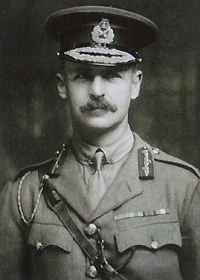

The idea of the Guards Division had been Kitchener’s and it seems that once he had The King’s approval, he went ahead with the arrangements without any discussion with the War Cabinet or the Commander-in-Chief. Indeed, the first indication that Sir John French had was a letter from Kitchener in July 1915 telling him of his plans and the name of the first GOC, The Earl of Cavan. Kitchener asked him ‘whether you like this idea’, but he could hardly have objected since The King had already been consulted. In any event, French’s position as Commander-in-Chief was becoming more strained. The Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, had recently been in discussions about French’s future and, just two weeks before Kitchener’s letter, The King had concluded that French should go.

On 16th July, Kitchener told Major General Sir Francis Lloyd to prepare the 3rd and 4th Grenadiers, the 2nd Irish Guards, and the recently raised 1st Welsh Guards for overseas service. The aim was for them to move to France immediately, where the Division would form up with those battalions already deployed. The Guards Division was to have ‘no number’ and would be quite distinct from others. Kitchener, who had been appointed Colonel of the Irish Guards on the death of Field Marshal Roberts in November 1914, was clearly enthusiastic about the idea of creating an elite division. In the words of the Guards Division’s official historian ‘The loyalty, the discipline, the devotion to duty and the proved efficiency of the Guards would be an example’ to all, in particular, perhaps, to the inexperienced officers, non-commissioned officers and soldiers of Kitchener’s New Armies.

But not everyone shared Kitchener’s enthusiasm. There was a view that bringing so many ‘fine battalions’ together into a single division was a mistake, and that it would be better for their high levels of training and discipline to be more evenly distributed across the BEF. Some Guardsmen felt that the demands of maintaining numbers in an entire division might undermine the Guards’ high standards. As one regimental historian commented: ‘If the division took a bad knock, the Brigade of Guards might be finished, but as it turned out the division took many bad knocks, but always came up smiling’. Whatever the reservations, the Guards Division formed up in France over the next two months, and was ready to be committed in September.

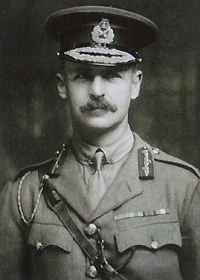

Major General The Earl of Cavan, Grenadier Guards Major General The Earl of Cavan, Grenadier Guards

|

Second Lieutenant M H Macmillan,

4 Company, 4th Battalion Grenadier Guards |

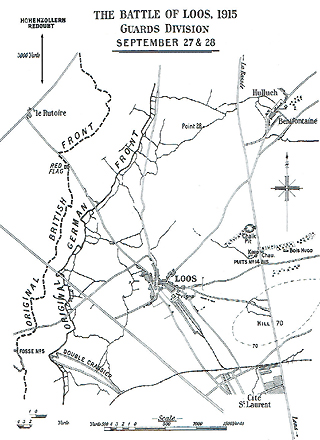

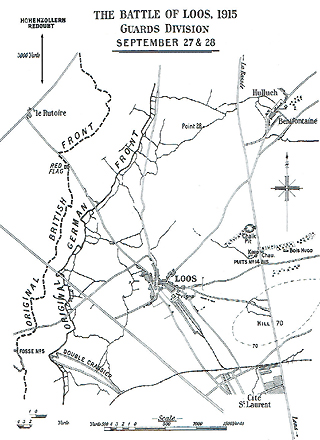

The plan for the ‘Big Push’ was for the British First Army to advance eastwards between La Bassée Canal and Lens, breaching the German first and second lines of defence and seizing the village of Loos and other strongpoints. As part of a wider offensive, Marshal Joffre envisaged a pincer movement that might trap the Germans or force them to withdraw from the Noyon salient or even push them beyond the Meuse to end the war. Joffre was confident that the British would ‘find particularly favourable ground between Loos and La Bassée’. Sir John French agreed, while Sir Douglas Haig, commanding the First Army, was concerned about the lack of heavy artillery and shells. Sir Henry Rawlinson, a Coldstream Guardsman and one of the Haig’s corps commanders, noted in his diary ‘My new front is as flat as the palm of my hand. Hardly any cover anywhere ... It will cost us dearly’. Haig, on visiting the area, recorded his view that ‘The ground, for the most part bare and open, would be swept by machine-gun and rifle fire ... rapid fire would be impossible’.

But Kitchener soon made his views clear: ‘... we must act with all energy and do our outmost to help France in this offensive, even though by so doing we may suffer very heavy losses’. The British attack on Loos would go ahead, regardless; the imperatives were political, and certainly not military. Haig decided to attack on a narrow front and with just two divisions, but the prospect of employing gas persuaded him to expand his plan to six divisions over a wider frontage. He requested that the reserves, the Cavalry Corps and XI Corps, with its three infantry divisions (the Guards, 21st, and 24th), be placed under his command before the battle. Sir John French refused, a decision that would later have grave consequences, for both the battle and his future as Commander-in-Chief.

The British artillery barrage began on 21st September, and at 5:50am on 25th September Haig ordered the release of gas from canisters in the front-line. The gas clouds lingered in No Man’s Land and in some places drifted back towards the British trenches, causing unnecessary casualties. 40 minutes later, the assaulting infantry began their advance across open fields, and despite heavy losses, by midday had captured the village of Loos and the Hohenzollern Redoubt just to the north. The 21st and 24th Divisions were now called upon to exploit this early success but, due to poor communications and planning, did not go into action until the afternoon of 26th September. Their objective was the strongly-held German second-line defences, and in the event the attack was a costly failure with both divisions taking huge casualties.

On 27th September, with the Guards Division now finally under Haig’s command, the 1st and 2nd Guards Brigades began to relieve the 21st and 24th Divisions with orders to consolidate the line. Harold Macmillan, who had arrived a few weeks earlier with the 4th Grenadiers, recalled the Corps Commander’s address prior to the move up to the front-line: ‘Behind you, gentlemen, in your companies and battalions, will be your Brigadier; behind him your Divisional Commander, and behind you all - I shall be there’. And then came the voice of a fellow officer saying ‘Yes, and a long way too!’ The Corps Commander was Lieutenant-General Haking and, in his various addresses he had displayed plenty of enthusiasm for the coming battle as well as confidence in a favourable outcome. This was going to be ‘the greatest battle in the history of the world’, and the victors would be the British.

But nothing was going right, and the call for the reserves had been unnecessarily delayed. Conditions for the relief were appalling, the battlefield was strewn with dead bodies and abandoned equipment, and the ground was muddy and slippery. But despite the confusion as the Guards moved forward in darkness, the relief was completed by dawn and they ‘had succeeded in making themselves as safe and comfortable as was humanly possible’. Early that afternoon Cavan was ordered to consolidate the British line, with 2nd Guards Brigade capturing Chalk Pit and Puits No 14.bis on the Lens-La Bassée road, 3rd Guards Brigade capturing Hill 70, and 1st Guards Brigade protecting the left flank.

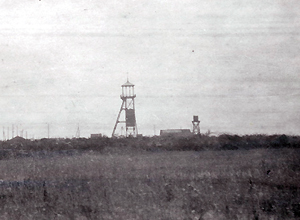

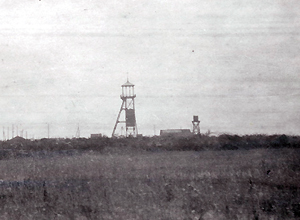

Puits No 14.bis

|

The support line, Chalk Pit Wood, 1915 The support line, Chalk Pit Wood, 1915

|

The ground was flat, and the area beyond the road was particularly exposed to German machine-gun and artillery fire. The three objectives could be clearly seen from where Brigadier-General Ponsonby, commanding 2nd Guards Brigade, issued his orders. It was a particularly bleak and unattractive view, not rolling countryside with conveniently placed cover and dead ground, but a stark coalfield dotted with odd buildings and slag heaps. Puits No 14.bis, was a pit head, with a fragile looking gantry for the winding gear silhouetted on the horizon, described by The Times Special Correspondent as ‘a conspicuous and ugly building with the usual lofty chimney’.

Two companies of 2nd Irish Guards moved off at 4pm, and reached Chalk Pit Wood with only a few casualties, having been protected by a smokescreen laid by the 1st Guards Brigade. They then joined 2nd Scots Guards as they ‘advanced in open order and doubled down hill under very heavy fire of shrapnel’. Reinforced unexpectedly by a detachment of 4th Grenadiers, the Scots and Irish then assaulted the ‘Keep’ and the Puits. A small party of Scots Guards managed to get inside the building where there was some ‘fierce hand-to-hand fighting with the Germans’ but casualties had been so heavy that success was not possible. Meanwhile, the 1st Coldstream following up the Irish Guards and the 3rd Grenadier Guards supporting the Scots Guards had come under fire as they advanced towards Chalk Pit Wood. A few Grenadiers managed to reach the Puits, but along with the Scots Guards were forced to pull back. By the end of the day 2nd Guards Brigade had achieved some success by securing Chalk Pit Wood, but at considerable cost, and the toll in officers was particularly high. Puits had been beyond their grasp. To quote the Scots Guards regimental history: ‘It was a great achievement, in the face of the terrible fire, to have gained the position at all; it would have been a greater one to hold it; for the position had been so completely prepared and covered by fire by the Germans that it was almost untenable by any British who got into it’.

Rudyard Kipling, in his history of the 2nd Battalion Irish Guards, quotes the war diary, describing how ‘some few Irish Guardsmen’, including his son John Kipling, had gone forward with the Scots Guards party commanded by Captain Cuthbert. This ‘rush’ of Guardsmen somehow made it to a line beyond the Puits, but in the face of heavy machine-gun fire. Captain Cuthbert was dead, young Kipling was wounded and missing, and the Scots Guards party fell back from the Puits ‘into and through Chalk-Pit Wood in some confusion’. But there were still some Irish Guardsmen beyond the wood; a little later a runner was despatched by Captain Harald Alexander ‘saying that he and some men were still in their scratch-trenches on the far side of Chalk-Pit Wood, and he would be greatly obliged if they would kindly send some more men up, with speed’, although as Kipling observes the ‘actual language was somewhat crisper’.

The 3rd Guards Brigade attack onto Hill 70 was to take place once Chalk Pit Wood and Puits had been captured, since the risk of enfilade fire from these positions was too great. The Brigade began their advance having been warned that as soon as they ‘appeared over the skyline beyond Fosse No.7 they would probably come under the enemy’s artillery fire’. The warning was to prove correct, but despite ‘a tornado of shrapnel fire’ in the words of The Times Special Correspondent, the Brigade ‘advanced with the steadiness of men on parade, and men of other battalions who could see the manoeuvre from their own trenches have spoken again and again of that wonderful advance as being one of the most glorious and impressive sights of the war, and how they were thrilled to see those large silhouettes pressing silently and inexorably forward against the skyline’. As the brigade advanced, to quote the Welsh Guards regimental history, ‘shrapnel burst, making puffs of smoke overhead, high explosive shells sent up sudden fountains of mud and black smoke which completely obliterated, according to the view-point, now one, now another of those small squares of advancing men, who, however, slowly and steadily continued to advance, the brigade covering a large area of ground in this formation’. A soldier watching from the nearby Royal Sussex trenches described their advance as bringing ‘tears to my eyes, men were dropping like flies but they kept on as if they were marching up the Mall’.

The Brigade managed to reach Loos in remarkably good order, although the 4th Grenadiers were met with a volley of gas-shells as they emerged from the communications trenches close to the village. In the confusion, as soldiers donned their Hypo Helmets, the Commanding Officer became a gas casualty and over half the battalion was separated from the remainder in the narrow streets. Harold Macmillan and his platoon were among them and, reluctant to crawl, he described ‘walking about, trying to look as self-possessed as possible, under heavy fire’. Another Grenadier officer saw the artillery commander in Loos ‘almost demented’ because of the lack of infantry in the village and then ‘regardless of shot and shell, Harold, aged 21, walked up and down the roads in full view of the enemy, holding the General by the arm and saying his men would be there in a few minutes and all would be well’. Macmillan had already been slightly wounded in the head, and was later shot in the right hand and evacuated. For a while after the battle, all acts of courage were rated by the 4th Grenadiers as ‘nearly as brave as Mr Macmillan’.

With the Grenadiers now much reduced in numbers, Heyworth decided to give the task of capturing Hill 70 to the 1st Welsh Guards, supported by the Grenadiers. Making the assumption that Puits had been captured by the Scots Guards, he briefed the Welsh Guards’ Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Murray-Threipland. The Welsh Guards had also experienced their first gas attack that afternoon as they struggled into their new ‘horrible slimy bags’, the Hypo Helmets. Captain Humphrey Dene later recalled the scene, as the battalion made ‘... noises like frogs and penny tin trumpets as they spat and blew down the tubes of their helmets [as] shells crashed into houses’.

Murray-Threipland went off to find the Grenadiers, made his plan and gave orders to his company commanders. The attack on Hill 70 began at 5:30pm and was underway when Murray-Threipland was informed that it was to be cancelled due to the failure to capture Puits. It was, of course, too late, and in the event good progress was made until the Guards reached the crest of Hill 70, when they came under intensive machine-gun fire. Private Britton described the experience ‘I was a bit flurried but soon got over it. We had to advance along a communication trench where there were most elaborately fitted dug-outs. I saw a dead German with his head and leg blown off’.

Despite the intensive machine-gun fire, the Welsh Guards and Grenadiers managed to get within 25 yards of the enemy position. Heyworth had given orders that no one was to go beyond the crest, but sadly the order had not been passed onto Major Myles Ponsonby, now commanding the Grenadiers. Consequently, they took very heavy casualties on Hill 70, including Major Ponsonby who was hit and died the following morning. His adjutant, Captain Thorne, who had dressed Ponsonby’s wounds as he lay just 25 yards from the German position, was killed later that day, trying to carry a wounded drummer to safety.

Sometime later, Murray-Threipland sent the message that Hill 70 had been successfully taken, requesting that 2nd Scots Guards should relieve the Welsh Guards and Grenadiers in order to consolidate the position. Lieutenant-Colonel Cator, commanding the Scots Guards, decided to establish a line 100 yards back since no proper digging could be conducted so close to the German position on the crest. The trenches were quickly dug and well wired, but the gathering-in of the wounded laying below the crest was all but impossible. The area was now more secure than before the attack, and the Welsh Guards, ably supported by the Grenadiers and Scots Guards, had seen action for the first time. But the losses in the 3rd Guards Brigade, particularly among officers, had been high, and the redoubt on top of the hill was still held by the Germans.

Lord Cavan decided that further attacks onto Hill 70 would serve no purpose, and so gave orders that the defences around the hill were to be strengthened. In the meantime, he received orders that the 2nd Guards Brigade was to conduct an attack onto Puits No 14.bis on the afternoon of 28th September. The Brigade Commander, Brigadier-General Ponsonby, believed that the attack had little chance of success, but since he had no communications with Lord Cavan, felt obliged to carry on. The attack was conducted by the Coldstream Guards, in the face of heavy machine-gun fire from three directions. A few soldiers reached the Puits, but the attack proved to be abortive, with 9 officers and 250 other ranks killed or wounded.

The Guards Division now consolidated their positions, extending their trenches to secure the new front-line. During the night of 30th September, and working throughout the hours of darkness, the 1st & 2nd Guards Brigades dug new trenches along the Lens-La Bassée road, linking up close to the Chalk Pit. Concurrently, the relief of the Guards Division began at midnight on 30th September, and was completed by 4am the following day, despite heavy shelling, appalling weather, and dreadful conditions on the ground. Three days later, the Guards Division was called forward again, this time to be prepared to conduct an attack onto the Quarries, over two miles to the north of its old positions. By 4:15am on 6th October, this complicated ‘side-slip’ of the brigades had been completed. Orders had also been received for gas cylinders to be brought forward to the front line in preparation for the attack.

Sometime around 4pm on 8th October, the Germans launched an attack along 2nd Guards Brigade’s front-line, with most of the attack concentrating just south of the Hohenzollern Redoubt. Two companies of the 3rd Grenadiers were attacked along a communication trench running east and west of their positions, and soon they had exhausted their supply of bombs. The turning point of the engagement came with the action of Lance Sergeant Oliver Brooks, Coldstream Guards, who organised a bombing party and proceeded to drive the Germans back, bombing them out of their trenches. By 7pm the line had been recovered and the Grenadiers were able to consolidate their positions. For this brave action, Sergeant Brooks was later awarded the Victoria Cross.

The official history identifies two factors in the reversal of fortunes that afternoon. Firstly, the action of the bombers so ably led by Lance Sergeant Brooks but also the supply of bombs from the 1st Irish Guards on their left which had allowed the fighting to continue. The relative ease with which brigades and battalions helped and supported each other demonstrated one of the advantages that the Guards Division had over others. Even though this was a new division, there was already a sense of unity and common training and a ‘feeling of confidence and pride which is bound up in the traditions of the Brigade of Guards’.

On 12th October, just before a planned relief, the Guards Division was again attacked by the Germans. Following a tough four hour battle, which combined bombing and the firing of trench mortars, the Germans pulled back having gained no ground and incurring heavy casualties. By 14th October, the Guards were again back in the front-line, preparing for another attack, this time onto the Dump and Fosse trenches. Conditions were appalling. To quote the war diary of the 1st Coldstream: ‘The state of the trenches was terrible, unburied bodies lying everywhere, and the parapets and communication trenches blown in on all sides. The trenches allotted to the battalion were knocked about and we found dead bodies, equipment and debris of all kinds mixed up together. Salvage parties worked all day. Just as much damage was done to the communication trenches as the front line trenches’. Digging was extremely difficult and dangerous. ‘Work could only be done at night’, as Evelyn Fryer, serving with the 3rd Grenadiers, described ‘and then one could only sap and not dig from the top, and the Germans were only a few yards off, and it meant certain death to show oneself’.

The Battle of Loos was not yet over. By 17th October, the 2nd and 3rd Guards Brigades were back in the front-line, preparing for an attack onto the Hohenzollern Redoubt. It began at 5am, supported by artillery and trench mortars. But in the face of intensive enfilade machine-gun fire, Lord Cavan called the attack off at 8am. The decision had clearly not been taken lightly. To quote the official history: ‘Some idea of the severity of the fighting may be obtained from the fact that the two Guards brigades between them made use of 15,000 bombs, while both brigadiers agreed that they had experienced no more heavy shell fire during the war than between dawn and midday on the 17th October 1915’.

The Loos offensive ended the following day. The British had begun with a numerical advantage, but the ground was far more favourable to the Germans, there were shortages of heavy artillery and shells, and the use of gas created as many problems for the attacker as the defender. The reserves had been held back from the front-line and remained under Sir John French’s orders for too long, a fact that Haig wasted no time in reporting to Kitchener: ‘No Reserve was placed under me. My attack, as has been reported, was a complete success. The enemy had no troops in his second line, which some of my plucky fellows reached and entered without opposition ...’ But by the time the reserves were ready to attack, it was too late. ‘…..We were in a position to make this the turning point in the war ... but naturally I feel very annoyed at the lost opportunity’.

There were other tactical lessons from Loos, but not all were identified at the time. The battle fits all the stereotypes by which a much later generation has judged the competence of the senior commanders, most notably French and Haig - ‘Lions led by donkeys’, as described by Alan Clark in his highly polemic book published in 1961. Commanders at all levels were struggling, and tactics were still evolving, but progress was to be slow. Rudyard Kipling expresses an understandable emotion in describing the fighting in which his own son John was killed: ‘So, when the Press was explaining to a puzzled public what a far reaching success had been achieved, the “greatest battle in the history of the world” simmered down to picking up the pieces on both sides of the line, and a return to autumnal trench-work, until more and heavier guns could be designed and manufactured in England. Meanwhile, men died’.

Lance Sergeant Oliver Brooks VC Lance Sergeant Oliver Brooks VC

Coldstream Guards

|

Second Lieutenant John Kipling Second Lieutenant John Kipling

Irish Guards |

The Guards had fought bravely at Loos, earning many fine tributes from observers, including The Times Special Correspondent. The words used to describe the Guards in action resonated with the image of the parade ground and public duties, faded picture postcards of tunics, bearskins, and soldiers marching steadily in perfect formation. The public back home would not have been disappointed. The battalions that had already fought in the front line, along with those that had just arrived, most notably the newly formed 1st Welsh Guards, had all performed well. But casualties had been heavy, particularly in the 1st Scots Guards, who had lost 474 soldiers. Many officers, pre-war regulars who had been fighting since August 1914, were now dead, and there was a gradual acknowledgement that the reserve officers replacing them were now earning their spurs at the front. To quote the official history, ‘After the Battle of Loos, even old-fashioned Guardsmen became convinced that officers of the Special Reserve could safely be employed as company commanders’. The reality was that from now on, and increasingly, it would be the reservists who would be in the lead, since so many of the old regulars were gone.

British losses at Loos were nearly 50,000, with 16,000 dead and 25,000 wounded. It was to be Sir John French’s last major battle. The knives were already out, and he was now left with few friends in high places. Criticism steadily grew in the weeks that followed, and the Commander-in-Chief’s official despatch, published on 2nd November 1915, did little to relieve the mounting pressure. By early December, French was appealing to Herbert Asquith, but the Prime Minister, now heavily influenced by the views of many others, made it known that French must resign, which he did. On 10th December 1915, Haig was informed that he was to be appointed Commander-in-Chief.

Six months later, on 6th June 1916, Sir John French was appointed Colonel, Irish Guards, succeeding Lord Kitchener who had been drowned the previous day when the armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire had hit a mine and sunk west of the Orkney Islands. Although some Irish Guardsmen became a little ambivalent about Sir John French’s legacy, he is now remembered for one important reason: he saved the Regiment from disbandment in the early 1920s. To quote the Household Brigade Magazine in 1925, following his death ‘... the younger generation of Irish Guardsmen should realise that had it not been for their Colonel’s determined stand through the controversy of 1920 their Regiment would by now have in all probability ceased to exist ...’. |

|

Major General The Earl of Cavan, Grenadier Guards

Major General The Earl of Cavan, Grenadier Guards Second Lieutenant M H Macmillan,

Second Lieutenant M H Macmillan,

The support line, Chalk Pit Wood, 1915

The support line, Chalk Pit Wood, 1915

Lance Sergeant Oliver Brooks VC

Lance Sergeant Oliver Brooks VC Second Lieutenant John Kipling

Second Lieutenant John Kipling