|

WATERLOO UNCOVERED

by Major C M J Foinette

Coldstream Guards

|

Waterloo Uncovered serving and retired Coldstreamers outside the North Gate, with Tim Jemmett, who led the team of craftsmen from the Petworth Estate who installed the new gates.

From left to right: Maj Foinette, Lee Spencer, Ben Hilton, Tim Jemmett, Mark Evans, Gdsm Douglas, Gdsm Buckley, Martyn Jones, Keith Hingle.

Not pictured: Dmr Birch and Gdsm Kent (David Ulke)

|

This summer, a team of archaeologists, veterans, soldiers and historical researchers began what we hope will be a long-running project. Waterloo Uncovered draws together the efforts of conflict archaeologists to shed further light on the events of 1815, whilst at the same time introducing serving and former soldiers to a new discipline. It follows an initiative begun several years ago in the UK and supported especially strongly by the Rifles. That project, ‘Operation Nightingale’, was a cooperation between the Defence Archaeology Group and various rehabilitation organisations, and allowed injured servicemen to experience archaeology for the first time, working largely on the MoD estate. Sites on Salisbury Plain, at Lulworth, near Catterick and even in Cyprus have been explored, with the subject matter as varied as Bronze Age settlements through to Second World War aircraft. Their experience has served to demonstrate two things: that archaeology is an interesting, challenging and stimulating way to contribute to the recovery and rehabilitation of injured personnel and that, with the correct level of expert supervision, very high academic standards may be achieved with work at sensitive sites.

In 2014, a small group began planning the Waterloo project as a follow-on to the success of ‘Operation Nightingale’. Mark Evans and I, both Coldstream officers, had studied archaeology together at UCL before joining the Army. He, subsequently, had a very difficult tour in Afghanistan that resulted, eventually, in a diagnosis of severe PTSD and his medical discharge. Over the years, we had discussed many times whether or not Waterloo was a site in need of proper investigation. Hougoumont, in particular, seemed a place that would be of natural interest to archaeologists, with a number of questions outstanding to historians about the precise layout of the chateau and grounds, the ebb and flow of the battle and of the dispersal of the debris and casualties afterwards. Most recently, the work of our colleague Dominique Bosquet led to the recovery of the only intact skeleton found on the battlefield, and of course the excavation of the Hougoumont well, in 1985, by Derek Saunders, succeeded in debunking Victor Hugo’s lurid accusations that French casualties had been thrown into it by the defenders. But other than these two notable exceptions, there has been very little detailed archaeology carried out at Hougoumont.

So it was that, with the encouragement and advice last year of those responsible for ‘Operation Nightingale’ and the support of key members of the ‘Project Hougoumont’ committee, we finally found ourselves moving beyond idle chat and into the realms of actually planning something.

The strength of Waterloo Uncovered, in our view, is that it is a partnership between individual institutions and advisors united by a shared interest in this fascinating place, but with bringing very different areas of expertise. We were very fortunate, therefore, to establish close links with Dominique Bosquet, who is the local government archaeologist for the area. He was enthusiastic about the project and, as part of the team himself, is able to overcome bureaucratic hurdles whilst ensuring that we comply with all local rules and policies and satisfy his department, the Service Publique de Wallonie. We were equally fortunate to find that Dr Tony Pollard, the Director of the Centre for Conflict Archaeology at the University of Glasgow, was just as keen and agreed to be our Archaeological Director. Other partners in the work conducted this year include the Coldstream Guards, the MoD, the University of Glasgow, Project Hougoumont, L-P Archaeology, and University College Roosevelt, in Holland.

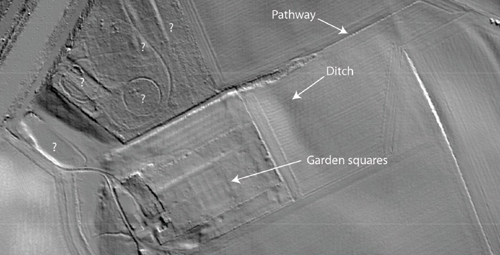

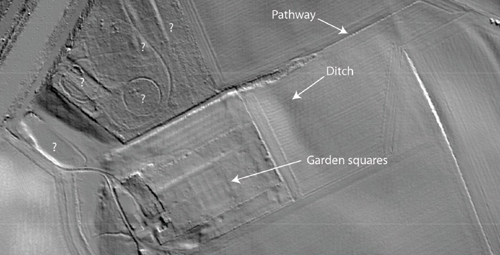

Just as Wellington did, we are drawing heavily on Dutch and Belgian expertise, especially in the field of geophysical analysis. The team from the University of Ghent who undertook the detailed surveys of the farm and its surrounds are amongst the very best in the business, anywhere in the world. The equipment that they use is so advanced that they have been contracted this summer to work on Stonehenge for English Heritage. Unsurprisingly, the results of their work at Hougoumont far exceed anything previously attempted and are very exciting indeed. Alongside that, Dominique’s colleagues have undertaken very detailed Light Detection and Ranging scans - a technique in which an aircraft or, in this case, a ‘drone’, carries scanning equipment that makes a minutely detailed measurement of ground levels using laser beams. The information allows ‘clutter’ such as trees, vegetation, buildings, etc, to be stripped away to reveal shapes invisible to the naked eye. This view of Hougoumont is especially striking as it shows outlines of the formal garden that are not only invisible on the ground, but almost impossible to discover (as we found) by excavation. These tiny variations in ground shape really are the last shadows of the features that were there two hundred years ago!

An image of Hougoumont created by using a scanning laser mounted on a ‘drone’ to record minute changes in ground level. All above-surface features, including vegetation and buildings, have been removed and the pattern of the formal garden that once stood within walls to the east of

An image of Hougoumont created by using a scanning laser mounted on a ‘drone’ to record minute changes in ground level. All above-surface features, including vegetation and buildings, have been removed and the pattern of the formal garden that once stood within walls to the east of

the chateau is visible (Service Publique de Wallonie) |

With all this behind us, we were able with some confidence to undertake preliminary work in April, leading to a full two-week excavation at the end of July. The first week involved a small group that included a metal detector survey team, some serving guardsmen from 1st Battalion Coldstream Guards and a number of veterans from other regiments. Through a combination of surface surveys, core (auger) sampling and the digging of test trenches, we evaluated the areas that appeared, on the geophysical surveys, to show anomalies of interest. The area to the south of the farm (the wood in 1815, but now open fields) was of particular interest, as it would be under crop when we returned. Finds in this area included French and British musket balls, including quite a number found right on the southern fringe of what would have been the wood and that may well represent the earliest skirmishes of the battle. Also found was the foundation of a brick kiln, rather older than the battle, that almost certainly dates from the original construction of the chateau in the seventeenth century.

Most importantly, the excavations allowed Tony Pollard to test the reliability of the geophysical survey and to plan for the summer. In July, we returned with a much larger team - some 45 people - that included both veterans and serving soldiers. The Coldstream, Grenadiers and Household Cavalry were represented in that cohort, as were the Rifles, Royal Signals, Royal Engineers and a number of others - even the RAF! Serving personnel attended alongside veterans, and we had personnel who had experienced both physical and psychological harm from service. During that fortnight, despite the very best efforts of striking French sailors to disrupt our endeavours, a huge amount was achieved. Most importantly, there were very few tasks that any of our participants were unable to carry out, though some visitors certainly appeared bemused by the sight of prosthetic legs discarded at the edge of a trench! The mix of soldiers, students and professional archaeologists seemed especially effective, and it was no surprise to see that guardsmen in particular had little difficulty in meeting the obsessive standards required for both cleaning and recording trench features. A detailed training syllabus had been prepared by the trench supervisors, and those who were new to archaeology were expected to have a go at everything from surveying to finds processing.

A French musket ball found in the ‘killing zone’ to the south of the garden wall. This one is distorted and has brick dust embedded in it, compelling evidence that it was fired against the wall held by the defenders (Tony Pollard)

A French musket ball found in the ‘killing zone’ to the south of the garden wall. This one is distorted and has brick dust embedded in it, compelling evidence that it was fired against the wall held by the defenders (Tony Pollard) |

In terms of what we found, there is rather too much to list here, but we can safely describe the dig as a success in archaeological terms. We found many, many musket balls, with the damage to them and distribution able to tell us a great deal about patterns of fighting. We have uncovered firm evidence for various tracks and boundaries that help to make sense of contradictory maps, and excavated the original level of the ‘sunken way’ - it is much deeper than it appears. Over the coming weeks, the excavation reports will be written and hundreds of finds will be made available for examination online, together with detailed maps and overlays of modern topography on a 3-D scan of Sibourne’s model.

Waterloo Uncovered has been an enormously enjoyable experience for all concerned. It could not have happened at all without the generous support thus far of our private donors, volunteers and charitable grants from the Coldstream Guards, Army Benevolent Fund and notable others. We intend to continue the project, if we can secure the funding to do so - there is a huge amount still to record on the battlefield, and growing recognition in the way that archaeology can both answer historical questions and help those injured in service to find new interests and skills. Next year, we may even have some French veterans!

Anyone who would like to follow our progress, donate to the project, or become involved, is encouraged to visit our website, www.waterloouncovered.com, or to look for us on Facebook.

The Waterloo Uncovered team in the garden at the end of the summer dig

The Waterloo Uncovered team in the garden at the end of the summer dig |

|

|