|

A SOLDIER’S RETURN

The Falkland Islands – 42 Years On

November 2024

by Major James Kelly

formerly Scots Guards

|

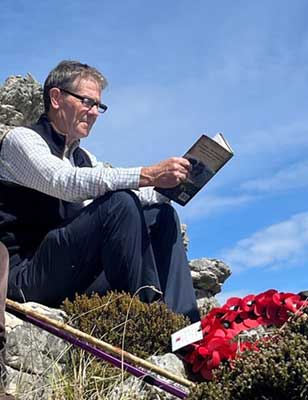

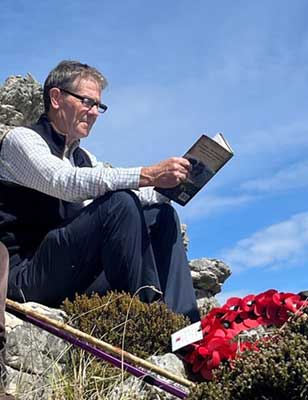

The author at the approach to the Two Sisters – unsuitably dressed!

|

Brigade Squad survivor (1983), Grenadier bursary at Oxford, chartered accountant, group finance director, and Boodle’s member; a rare combination for a Senior Aircraftman in the Royal Air Force Reserves. But Simon Miesegaes (‘Meezygas’) embodies all of that. A meticulous organiser with encyclopaedic knowledge of aircraft loading drills, flight schedules, and with a 2022 Falklands deployment under his belt, he was the ideal leader for a visit to the Islands.

I had met Simon, by chance, shortly after he returned from the Falklands in 2022. He was dining with friends and, once he had heard that I had commanded 1 Troop, 45 Commando on Two Sisters in 1982, he insisted that I join them. When I explained that I had never been back to the Islands, he simply said that we needed to change that and that he would put something together. Lord (Maurice) Fermoy, formerly The Blues and Royals and Rupert Uloth, formerly The Life Guards, were Simon’s contemporaries at Eton, and with a shared interest in military history. With Simon’s stories of his time there, told on the hunting field or over lunch in a London club, Maurice and Rupert were eager to accompany him on a return trip.

The first meeting of the four of us was over a splendid lunch in Boodle’s, and after about three hours of stories and laughter, it was clear that we made a rather good quorum. We would all go together, and Simon began his meticulous planning. He knew the best battlefield guide on the Islands, the best wildlife tour guide, the Commander British Forces, the most suitable accommodation in Stanley (Shorty’s Motel), and also the best type of four-wheel drive car to book for our tour. More convivial club lunch meetings followed, as well as Simon’s detailed itinerary.

The trip would be arranged around Remembrance Sunday, and with this important date in mind, ASI Miesegaes booked the most comfortable RAF seats available for the 18-hour flight to the Falklands, via Ascension Island. As a member of The South Atlantic Medal Association), my flight was much cheaper than the commercial rates, and I am forever grateful for the generous deal that enable veterans to return to the Islands at hugely reduced rates.

|

|

| Then and now. The same rock on the Two Sisters’ southern peak. 1982 and 2024 |

Arriving at Mount Pleasant Airport, our four-wheel drive truck awaited us in the car park (a joy that cars here can be left unlocked with the key in). Except for a stretch of road under repair, we had a smooth journey to Stanley: no potholes or traffic, vast grasslands, grazing sheep, and rugged rock features. Approaching Stanley, distant crosses and memorials began to appear.

En route, Simon made an unexpected detour to my X-Ray Company’s Assembly Area for the 1982 assault on the Two Sisters. The open ground we had crossed with bayonets fixed, under bright moonlight and through the freezing Murrell River to the spiny ridge of the mountain, lay before us. Standing in my New & Lingwood brown tassel loafers, it was not the time to venture further. A full tour of the battlefield was planned when we would certainly be better equipped and shod.

Stanley, the capital, has grown but from the air remains a small town. The Falklands Islands are about half the size of Wales, with a civilian population of 3,600 compared to 3.2 million for Wales.

Our first day was an opportunity to orientate ourselves. An excellent museum on the shoreline covers every aspect of island life, the 1914 naval battle, the 1982 war, and economic aspects like fishing licenses and wool.

At the Stanley War Memorial and Garden of Remembrance, we paid tribute to the 255 British Service personnel killed during the war and the three female islanders killed by shellfire during the final battle around Stanley. The nearby Task Force Memorial lists every ship, unit, and fatality, while a bronze bust of The Iron Lady stands proudly on Margaret Thatcher Drive, defiantly looking out to sea.

The following morning, with a packed lunch and a full tank of petrol from the only petrol station on the Islands, we began our tour. The plan was to retrace, in reverse, the Commandos’ famous ‘Yomp’ in 1982. ‘Yomping’ (from the Norwegian ‘Kyomping’), was the Royal Marines’ word for marching while the Paras, of course, ‘tabbed’. En route, Simon showed us the site of a crashed Argentine Chinook and Puma (shot down be a Sea Harrier), the wreckage still recognizable. Two locals stopped their vehicle on seeing us, the first example of what Simon called the ‘double handshake’: the local’s left hand also grasping my right hand, followed by a ‘thank you for what you did for us’ – that sat very deep with me.

East Falkland’s road circuit, the ‘M25’, is mostly gravel except between Stanley and Mount Pleasant. Arriving at Teal Inlet across vast, empty landscapes and sea inlets, we met a charming couple who gave us coffee and biscuits in their caravan; he had driven tractors during the war to help the British effort. We visited the memorial for those who died at Teal Inlet, mostly from wounds in the dressing station. We saw an old Royal Marines rigid raider, now used for crabbing and lobster pots. In the large sheep shearing shed, I took a photograph of the exact place that we had our one night out of the elements in 44 days, in soaking wet sleeping bags among the wool and sheep droppings. In 1982, it was luxury!

|

|

| The Teal Inlet sheep shearing barn in 1982. Our only night of shelter in forty-four days ashore. And the same spot in 2024 |

We moved on to Douglas Station, where we had spent a night during the Yomp in hastily dug shell scrapes with no cover. Then onto San Carlos (Blue Beach) where, overlooking Falkland Sound, is the immaculate Commonwealth War Grave Cemetery. Buried here are fourteen of the 255 British casualties killed during the war. Among them are Lieutenant Colonel H Jones VC OBE, and 2 PARA’s A Company second-in-command, Captain Chris Dent. It is a very peaceful place.

We drove on to a small farm close to Ajax Bay (Red Beach). The road was closed but we were told that if we approached Mrs Dickinson at the farm, she may allow access for a ‘1982’ veteran. We knocked on her door, explaining that this was my first visit since landing there in 1982, and she graciously let us in. In broad daylight, dry underfoot, and with nothing heavy on our backs, walking from the Land Rover to the beach, just under 1000 metres away, was heavy going; the rock runs are brutal, crevasse like at times. One can only imagine what it must have been like in pitch black, well below freezing, soaking wet underfoot, and with a heavy pack, not knowing if the enemy was about to open up on us at any moment!

|

Whale Bone Arch at Stanley Cathedral.

Left-to-right: Rupert Uloth, Simon Miesegaes,

the author, Maurice Fermoy |

A small cairn on the beach marked where we had landed and where four Royal Marines had later died in Argentinian air attacks. Some Brasso and a cloth ensured that the plaque was given a good polish in time for Remembrance Sunday. The derelict remains of the old lamb freezer factory were much bigger than I remember, while the bay seemed smaller. Our trenches were just up the hill, where we spent a week observing the air attacks in bomb alley and the sinking of HMS Antelope. When we heard we had also lost HMS Coventry, Sheffield, Ardent and SS Atlantic Conveyor (with three of our four Chinooks on board), one ‘wag’ commented that we would probably be ‘Yomping’ all the way to Port Stanley. None of us knew how prescient that remark was to become!

The following day was Remembrance Sunday, dressed in our dark suits, medals and Regimental ties. The four ‘Tweed Caps’ had been spotted in town by some locals who wondered what we were doing there. Now the mystery was solved, as we attended a packed service in Stanley Cathedral before marching with Service personnel from the Mount Pleasant base, the local Falkland Islands Defence Force, Cubs, Scouts, Veterans and others to the War Memorial. The Governor, Commander British Forces, and others, including me, laid our wreaths at the foot of the cross. It was an immaculate service, and afterwards we were invited for a drink at the Falkland Islands Defence Force’s base in Stanley, followed by the Royal British Legion’s headquarters.

The next day we met our guide, Tony Smith, who took us to the Argentinean Cemetery, and then the start lines for the Battle for Darwin and Goose Green. It was 11th November, Armistice Day, so it was important to stand in silence at 11am to reflect on the sacrifices made in 1982 and the many wars before and since. With Goose Green in the distance, it was as special a place as any on such an occasion.

While there, we contemplated Lieutenant Colonel H Jones’ act of gallantry which led to his death and posthumous Victoria Cross. Was this a display of all the best qualities of leadership, or was he just foolhardy? Simon (who had been here in 2022) brought the moment alive. Calling us to silence, as we huddled on the very spot from where H Jones launched himself forward, he begged the question ‘What would you have done?’, to which we had no answer on that crisp November day. Simon surmised that with losses mounting, with his Adjutant and A Company’s second-in-command killed in front of him, H Jones had no other option. Perhaps he was too far forward to make a considered decision, but it was too late; he had to act swiftly, leading by example. We stood on the darker grass that covers the trench from where the fatal Argentine gunfire came. In the dawn light H Jones was the perfect ‘short range’ target. We concluded, as we stood there, that every Sandhurst commissioning course should visit the Falklands battlefields, forming their own ‘huddles’ to debate this Goose Green leadership question. It was too good a ‘real life’ situation for young officers to miss.

|

The author laying a wreath at the Cenotaph, watched by the

Minister for Armed Forces, Luke Pollard |

|

The spot where we quietly stood at the 11th minute of the 11th hour on 11th November, Armistice Day. Goose Green Settlement is in the distance between us, with 2 PARA’s objective a long way off |

|

At Government House to present an album of

1982 photographs to The Governor,

Her Excellency Alison Blake CMG |

The most striking feature of this battlefield is its size. While the others have larger objectives, with craggy mountain tops, here the ground extends forever, over huge distances. When the battle was over on 29th May 1982, 2 PARA had lost eighteen men, with more injured, while the Argentinians had lost 55 and nearly 1000 prisoners. Brigadier Julian Thompson, commanding 3 Commando Brigade, later said that it was a battle that he had not needed, but in other ways it was an important victory. It raised morale, showing us all that victory was possible.

Back in Stanley, we had tea with the Governor, HE Mrs Alison Blake CMG, presenting her with a bound album of photographs taken in 1982 together with a framed Falklands map signed by the 168 veterans and family members who had visited in 2022. Simon had auctioned the framed map for Walking with the Wounded at their 2022 Christmas drinks party at The Cavalry & Guards Club, and it was bought (and then donated) by Patrick Waters (the eldest son of General Sir John Waters, Deputy Commander Land Forces during the Falklands War).

Back in 1982, following our Yomp from Port San Carlos (110 miles + 110 lbs of kit on our backs), 45 Commando were at the foot of Mount Kent, despatching fighting patrols to dominate the ground. My troop’s objective, with a full fighting patrol, was Estancia House, a settlement to the north, but thankfully it had been abandoned. Two similar patrols, in the confusion of darkness and fog, tragically opened fire on each other, with the death of four Royal Marines. Another was tasked to observe the foot of the southern of the Two Sisters, to inflict casualties if necessary and to safely return. A section of my troop went with them to recce the route before our main assault a few days later.

Brigadier Julian Thompson planned a full silent night attack with three objectives on the night of 11th/12th June. To the north 3 PARA would take Mount Longdon, in the centre 45 Commando RM would take the ‘Two Sisters’, and to the south, 42 Commando RM was to take Mount Harriet. With Tony Smith, at Mount Longdon, we walked the feature in reverse before retracing the route of the advance and the fighting. It is a huge mountain and because an unfortunate Para had stood on a mine during the advance, surprise was lost. Tony, who knew all the battlefields extremely well, said that this was the most chaotic, with no accurate account of what happened there. When 3 PARA veterans later walked the route with him, accounts and recollections varied. It was a long and hard-fought battle, with 23 British soldiers killed and nearly 50 wounded. Two of the PARA fatalities were just 17 years’ old. A third was killed on his 18th birthday.

|

On the highest point of the southern of the ‘Two Sisters’, Simon reading an account of the attack from Ian Gardner’s book The Yompers |

Sergeant Ian McKay was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for his actions on that night. We walked the presumed route of his assault and saw three places marking where he possibly fell. As a 27-year-old sergeant, he was the senior and oldest of them all, and who can say that any of them were more or less brave than the others. It was the collective view of all five of us that this VC was awarded to McKay for the efforts of all those who fought and died that night.

From Mount Longdon, Tony drove us to Mount Harriet, where 42 Commando had conducted a thorough recce of the feature and its approaches. The Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Nick Vaux, devised a simple and measured plan for the assault, striking hard at the rear of the enemy. On Mount Longdon, also a huge feature, but with the element of surprise, a good diversion plan, the cover of darkness, and determined troops, the attack succeeded with the loss of only two Royal Marines corporals. An astonishing achievement.

That same night, elements of 45 Commando Group marched through mist and fog to their assembly areas. The plan was for X-Ray Company to take the southern of the Two Sisters, and, once secure, to provide fire support for Yankee and Zulu Companies assaulting the northern Sister. Due to difficult conditions and a slight veering off course, X Company’s advance was delayed and so the two assaults went in simultaneously, although Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Whitehead’s reassuring voice on the radio seemed unperturbed. As we left the forming-up point, we fixed bayonets and crossed the start line as the mist disappeared and a full moon illuminated the ground ahead. We knew the enemy had been on the forward edge of the southern Sister as a patrol had earlier killed some of the Argentinians there. As we crossed the open ground and the Murrell River, we had expected to be engaged by direct and indirect fire, but without any shots fired, we began clearing the rough ground ahead. To our amazement, all we found were abandoned dead bodies.

On reaching the limit of exploitation on my first axis, I gave the code word ‘Boot Pot secure’, and 3 Troop moved through us, to be followed by 2 Troop as it was to their objective that the enemy had withdrawn. It was here that some fierce fighting took place, supported by the Company Sergeant Major’s GPMG support group. By dawn the position was taken, without a single Royal Marine lost. In the meantime, Yankee and Zulu Companies had also taken their objectives, albeit with four soldiers killed. Still, a remarkable achievement, considering the size of the objective and the length of time the enemy had to prepare their defences.

We then walked the southern feature, and its scale amazed us. We crossed the saddle between the Two Sisters, where Curly Elstow, a former Royal Marine, has built a memorial cairn for the four soldiers lost there. On the northern Sister, Tony showed us the route taken by Yankee and Zulu Companies. Even with light packs and walking sticks on a clear day, the terrain was tough, a sharp reminder of the conditions in 1982.

|

The crags of Mount Tumbledown are huge. It was here that young Scots Guardsmen, on ceremonial duties a few weeks earlier, fought in the dark, with bayonets fixed, in close-quarter battle. A humbling thought for us standing there 42 years later, on a warm and sunny day, with no weight on our backs. Eight Scots Guardsmen and a Royal Engineer died that night, and many more were wounded. The regular Argentine troops put up a determined defence, aided by heavy 0.5 machine guns |

We then spent a day looking at the wildlife, accompanied by Adrian Lowe, who farms 50,000 acres at Murrell Bridge, where penguins nest among sheep. Driving over rugged tracks, we visited penguin nesting sites. That evening, we dined with Brigadier Dan Duff, the Commander British Forces, and his wife, Billa, enjoying a 13lb sea trout that she had caught earlier.

The next day, we visited Mount Tumbledown, where Lieutenant Colonel Mike Scott led the Scots Guards’ assault on 13th June 1982, the last battle of the war. There was fierce overnight fighting here, with the loss of eight Scots Guardsmen. The battle is also remembered by Pipe Major Jimmy Riddell’s tune, The Crags of Tumbledown, which remains iconic.

We also visited West Falkland, driving four hours to catch a ferry to Port Howard. Although no formal battles occurred there in 1982, SAS contributions, including Captain Gavin John Hamilton’s daring missions, were vital. Tragically, Hamilton was killed there, earning a posthumous Military Cross. Critta Edwards showed us where Hamilton fell and where he is buried. Brigadier Duff and the team conducted a ceremony there in freezing rain.

Staying at Port Howard Lodge, a Highland-style retreat, we enjoyed a comfortable dinner. Next, we visited Shallow Water Farm at West Falkland’s edge, hosted by Ali and Marlene Marsh. The farm felt like the end of the world, with everything homegrown, a refreshing escape.

Back in Stanley, I gave a talk about my wartime experiences at the Mount Pleasant Officers’ Mess. Many questions followed, and it seemed that only a few had walked the battlefields.

For our final day, Simon surprised us with an aerial tour of East Falkland aboard a twin-propeller Islander aircraft. The captain, Andrew, who had lived most of his life on the Falklands, expertly answered questions while flying over battlefields, landing sites, memorials, wildlife colonies, and farms. There was no way better to tie in everything that we had seen. All in all, a brilliant finale.

|

|

The end of the Yomping - walking into Stanley in 1982, and the same spot in 2024! |

|

|