|

Home | About Us | Subscribe | Advertise | Other Publications | Diary | Offers | Gallery | More Features | Obituaries | Contact

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

This

is the law of the Yukon, and ever she makes it plain,

At

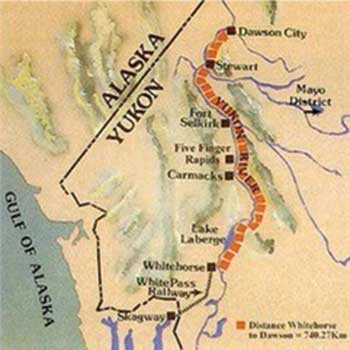

midday on 8th June 2022, a team of eight Grenadiers set

off in open canoes from Whitehorse in the Yukon Territory,

Northwest Canada, heading down the River

Yukon. The plan was to get to Dawson City, which is

located about 740 km north, having paddled the whole way

without any support, through one of the world’s last great

wildernesses. What is remarkable about this adventure is

that five members of the team have mental or physical

injuries, sustained

on various operational tours during their service in the

Regiment. At

midday on 8th June 2022, a team of eight Grenadiers set

off in open canoes from Whitehorse in the Yukon Territory,

Northwest Canada, heading down the River

Yukon. The plan was to get to Dawson City, which is

located about 740 km north, having paddled the whole way

without any support, through one of the world’s last great

wildernesses. What is remarkable about this adventure is

that five members of the team have mental or physical

injuries, sustained

on various operational tours during their service in the

Regiment.The expedition was the brainchild of Major Jon Frith (still serving and the team’s only veteran of the Yukon) and Lieutenant Colonel Guy Denison-Smith (who served 1991-2017). It was 18 months in the planning, with the ‘sword of Covid’ hanging over us throughout; we didn’t know until two months out if we could proceed. Then the green light was given and proceed we did; the start date was set for June this year, when usually all Guardsmen are settling down in front of the telly to closely watch and inspect the Trooping the Colour. We didn’t have that luxury! Along

with Jon and Guy, the others in the team were Paul

Richardson (PTSD; served 1984-95), Captain Ben Stephens

(1990-97), Alex Harrison (blindness; 2003-09), Dougie

Adams (PTSD; 2005-14), Captain Garth Banks (double

amputee; 2009-14) and Tony Checkley (single amputee;

2009-15). We ranged in age from 32 to 58 and, between

us, have served on deployments to Northern Ireland,

Bosnia, Iraq and Afghanistan, across 99 years of

service.

Having

completed over 120kms, we established our camp on a

small island in the river, safe from bears and without

vegetation, so it was nearly mosquito free.

However, we soon realised that the river hadn’t

finished rising! With the water level steadily

increasing, it became apparent that we might be washed

away and so we ‘stagged on’ throughout the night, to

ensure that we were not caught out. By 5am it was time

to abandon our much-reduced island and to head off,

whilst we still had time to pack up the camp first.

Leaving

Rita proudly flying a Grenadier flag that we had donated

to her and wearing one of our caps, we bade farewell the

following morning to tackle Day Six. The water level was

still rising as we headed for the junction of the Yukon

and White River. Along the way, we were joined by a

moose who had decided to swim across our path. At this

point the river was at least one kilometre wide; so it

was a truly sensational sight and the noise it made was

also extraordinary. We camped that evening at a place on

the map called ‘Thistle’ finding a navigable exit that

some local gold prospectors had forged into the dense

forest. Many still search for ‘Yukon Gold’, hoping to

make their fortune. For us the evening passed without

incident and we left the following morning, knowing that

we had only 200 kms remaining to cover before we would

reach our final destination.

We

woke on our last morning with 50 kms to go to Dawson

City and were joined for breakfast by several

inquisitive beavers. After packing up our camp for the

last time, the canoes were made ready and we headed off,

arriving at our destination by midday, feeling tired but

elated. The

sense of achievement amongst us was huge. The team had

overcome every obstacle together – every man played his

critical part. For

the briefest of moments it felt like we were all serving

again, working together in a close-knit team, dependant

on one another and only ever having to think about food,

shelter, survival and the task at hand.

Living under the never setting sun, in a vast,

unfamiliar territory with every sense straining to

distinguish if the noises of the wilderness were friend

or foe, we had come out the other side.

We had taken on Mother Nature and learnt to go

with the flow... literally. This was a truly memorable

experience for all of us and it shows that, disabled or

not, together extraordinary things can be achieved. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||