|

A WINDOW INTO A LIFE

WRITING MY MEMOIRS

by Field Marshal Lord Guthrie Of Craigiebank GCB GCVO OBE DL

Welsh Guards

Colonel of The Life Guards 1999–2019 |

George Orwell once said, ‘memoirs are only to be trusted when they reveal something disgraceful. A man who gives a good account of himself is probably lying’. 2020 was a year of precious few blessings but, like most people during last year’s longueurs, I found I had time to kill. Although I was now in my 82nd year, my thoughts turned to times past.

I have been reluctant to write my memoirs, not least because I have been extremely fortunate. I had no wish to break the Omerta, the code of silence in an honourable profession where many have lost their lives or continue to suffer to this day from the physical and mental scars of service to their country.

I should also add that I am on record as saying, ‘when I retire, I certainly will not be writing my memoirs. I’m sick of generals who write about their experiences in the Army. It’s a betrayal and should not be allowed. I’ll never write about my career and I don’t think others should either’.

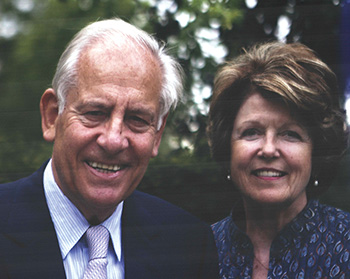

Charles and Kate. 2014 Charles and Kate. 2014 |

Despite my reluctance to write anything down, my family, friends and my regiment convinced me that I had good stories to tell and some common-sense advice to share. It was sometime in the spring of the first lockdown that I decided it was now or never. As so often in life, it was a chance comment that took the edge off my reticence. My eldest grandchild, Archie, who was in the habit of dressing up in combat kit whenever he came to see Kate and me, asked me a variation of that age-old question ’what did you do in the War, grandpa?’ It was time to marshal my thoughts.

My memory is the only diary I have kept. The memory of some of the 42 years I had spent as a soldier had slipped like sand through my fingers. The fall on my head as Colonel of The Life Guards in the 2018 Trooping the Colour has given me moments of great lucidity on events long past, mixed with what I can only describe as unnerving ‘senior moments’ about what happened last week.

A fifty-year marriage brings with it the gift of shared memories and Kate’s masterful collection of 60 photograph albums. They were a wonderful prompt as well as a joy to revisit. I was also able to call up strong mobile reserves, those dozen or so ADCs and military assistants who had served with me from my time as a divisional commander to Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS). I may have done important jobs, but they made sure I never took myself too seriously. Their recollection of the more absurd and humorous times we spent together in 23 countries has given me some memorable anecdotes.

The first question I had to ask myself was why should anyone bother to read my memoirs?

Once again, I had to remind myself that doing important jobs does not necessarily make for a good story. Portentous titles like Taking Command or Leading from the Front which my successors had chosen for their memoirs were not for me.

I had much enjoyed the former Grenadier officer, Patrick Hennessey’s account of his time in Afghanistan, The Junior Officers’ Reading Club. It was a human story, free of chest-thumping and allowing the reader to feel that Patrick’s experiences were not too far removed from the trials of any professional life. Of course, there’s a huge difference in perspective between the life of a platoon commander and that of the CDS. But they both face challenges which any soldier will understand: selection and maintenance of the aim, getting the best out of people, and building trust in one’s leadership.

It was predictable but nonetheless disappointing that some potential publishers were only interested either in eye-catching headlines, such as ‘Field Marshal blasts MOD over mishandling of helicopter support’, or worse still, now that it was twenty years since I had served, my views on the Army’s future strategy in the context of cyber warfare. I was reminded by my ADC at the time, Richard Stanford (now a general) that, as Chief of the General Staff (CGS) Richard had to teach me how to switch my computer on.

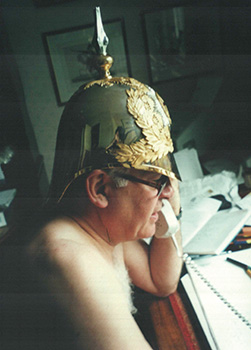

Captain Poldark. Adjutant. Aden 1965 |

Commanding Officer 1st Battalion Welsh Guards, with Margaret Thatcher in South Armagh. December 1977 |

Memoirs are not for settling scores, betraying confidences, or throwing people under a bus. People often remark to me that, when reading the memoirs of someone they know, they go straight to the index to see if they have been mentioned. After that, it’s the photographs and then a cursory read for the anecdotes and vignettes that make for a good story. I discovered early on in my career that you learn from others as much about how not to do things as how to do things well. There was only one person, a politician, whom I was rude about, but my views on this individual and his lack of support for the services were common enough currency at the time.

Memoirs are different from autobiography in the sense they do not need to be chronological. But they do have to have a certain flow otherwise readers will find themselves hopping about wondering what decade they are in. There were periods in my career that I consciously chose to leave out because they were plain dull; Assistant Chief of the General Staff was one; or because they added little to a reader’s enjoyment or curiosity. My time as the Corps Commander in the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR) differed little from my period as a brigade or divisional commander. The big step, and one which I decided to write about, was my appointment as Commander in Chief BAOR and Commander Northern Army Group. With a British, Dutch, Belgian, and German Corps under command, I became as much a diplomat as a soldier.

Memoirs are an expression of thanks. I joined the Army in 1959 for sport, friendship, travel, and the spirit of adventure. I had no greater ambition. The reason I decided a few years later that I could make a go of things was in no small part due to my formative years. In my Sandhurst intake were four other future Army Board members, all of whom became good friends: Willie Rous (Colonel of the Coldstream Guards 1994-1999), Mike Wilkes, Anthony Blacker and John Wilsey. My first four commanding officers in the Welsh Guards were all men of a different hue but with one shared characteristic: they had all fought in the war with the Guards Armoured Division. They looked at peacetime soldiering with bored amusement, but they cared about the Guardsmen and the officers. They were, without exception, extraordinarily generous to me of their time and advice.

People get hot and bothered, and rightly so, if you write indiscreetly about the SAS. As CGS I had to tell General Sir Peter de la Billière that he was no longer welcome at Hereford because he had crossed the line in his autobiography. I was able to write about my time in the late 60s as an SAS troop commander in Aden, Malaya, and Kenya, because the low intensity operations of that time are now well known. It was also a period rich with anecdote and characters of the brightest colours. Today, time spent in Special Forces is almost mandatory for high command. In 1968 when I embarked on SAS selection, the SAS was seen by many as a haven for mavericks who were a menace in the officers’ mess or just a plain nuisance. Once again, I was blessed with good fortune in my first squadron commander, the white haired and granite tough figure of Murray de Klee from the Scots Guards. He taught me the single most important lesson of my military career: to lead and manage others, you first need to manage yourself.

CDS with Tony Blair, in Kosovo. 1999 |

In New Zealand on a visit as CDS. September 2000 |

In the uncertain hours of the early morning, I still occasionally wake with a start after a dream where Field Marshal Lord Carver is hovering over me, expressionless, ‘I want next year’s financial projections for BAOR when I return from lunch’. In his own inimitable way, Carver, as CGS, was ferocious but fun and more than worthy of a chapter in my memoirs as his military assistant. From then on, I always found the labyrinthine ways of the MOD easy enough to handle.

In my memoirs I wanted to give a voice to people you do not expect to hear and to episodes that may seem strange, even shocking, but which reveal a truth about the human condition. I have a medal which is day-glo yellow. It always attracts comments and beady looks when I wear it. I see people muttering, ‘Mmm, how on earth did he get that medal?’. In 1980, in one of those eccentric throwbacks to the British empire, I found myself as Commander South Pacific with 42 Commando Royal Marines and the French Gendarmarie putting down a rebellion by local tribesmen in the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu).

By my early 40s, through good fortune, I had acquired the breadth of operational experience and staff work to make a success of the higher reaches of the Army. ‘I remember saying to the current Brigade Major, Guy Stone, just before he took up his appointment, that the hardest I’d ever worked was when I was Brigade Major. Guy looked askance, but after three years in the job he will now understand what I meant.

Concurrent activity. Training for the Queen’s Birthday Parade while talking to the Pentagon

|

In BAOR, the ritual dance of deterrence, garrison life, the Rhine Army Summer Show and autumn exercises, was not unlike life in the Raj. It was a pattern of life and behaviour that, once mastered, never left you, which is why, in my memoirs, I only covered in depth my time as a brigade commander. During that period, I served under and learnt a good deal from Nigel Bagnall, commanding 1st British Corps. He was a tough customer, not quite as acerbic as Carver but a pretty dry stick, so tone deaf he had to be prompted to stand to attention at the national anthem. He shook BAOR out of its torpor and unimaginative belief in forward defence. My time as a brigade commander was also my last command when I got to know a good many people and could make a genuine difference to their lives and careers.

There is a difference between good fortune and luck. The former maybe about a good posting at the right time or serving under a good leader who takes the time to mentor you; the latter is about a chance of fate. If you recognise the difference, you will see that self-regard has no place in memoirs. When the heroically named Lady Bienvenida Buck had an affair with Air Chief Marshal Sir Peter Harding, the then CDS, the carousel changed direction abruptly. Within 24 hours I found myself CGS with an easy enough leg-up three years later to CDS as the Army in the late 90s was doing all the heavy lifting.

I allowed myself one chapter in my memoirs on ‘Reflections on Command’. Much of what I wrote is common-sense advice for any army officer that I took from my lectures to the Staff College. There’s just one thing I observed in my contemporaries who never reached their potential and I proffer as advice to those who want to succeed: leave your ego on the wave behind you and take the time to get on with, and look after people, whatever their position or rank. If I may allow myself one pat on the back it is that 13 officers who served directly for me reached the rank of general.

I am proud to be the first Guards’ Field Marshal since Earl Alexander of Tunis. Given the size of the Army, I am almost certain to be the last. In a few decades, I’ll be a footnote in the history of the British Army. For my descendants, my memoirs have opened a window on my life into which, I hope, they will look with great pleasure. As for George Orwell’s dictum that memoirs should not be trusted unless the writer reveals something disgraceful about themselves, I shall leave that for others to judge. |

|