|

Nine Months with the Somali National Army

by Lieutenant Colonel C T Sargent MBE

Welsh Guards

|

The Foot Guards in Somalia. Lieutenant Colonel Chris Sargent WG and Major Paul Downes CG

The Foot Guards in Somalia. Lieutenant Colonel Chris Sargent WG and Major Paul Downes CG |

When one hears of Somalia, one may be forgiven for thinking of a nation state defined by conflict, civil war, famine and human misery. Often labelled as the most dangerous country in the world, Somalia has experienced much hardship over the past thirty years and is still a country that may characterise the idea of a failed or failing state. There is, however, an air of optimism and despite its recent violent history, Somalia may just be displaying the seedlings of the potential for a brighter future.

I arrived at Mogadishu International Airport in May 2019 for a nine-month tour as the Commander of the Somali National Army Support Team (SST). The team’s mission: to enhance the Somali National Army’s (SNA) ability to provide security and to support a fledgling Federal Government of Somalia (FGS). The command title is perhaps grander than the reality, with a team of some 25 officers and soldiers from across the Army; my command was slightly less in terms of mass than my platoon in No 2 Company, 1st Battalion Welsh Guards when I arrived in Newtonhamilton in 1997! The overall objective in essence is very simple: to make the SNA better and to give them a chance of a more stable future, although the reality is much more complex and challenging. In a country where government is fractured and scarred by clan dynamics and a violent history, even the most basic of human needs is a challenge. Facing a daily threat of violence and localised defeats from a ferocious and ruthless Al Shabab led insurgency, there is a mountain to climb in terms of security provision and a conduit to a more secure future.

Operation TANGHAM, the British mission in Somalia, includes a number of sub missions under one unifying Headquarters. Commanded by a British colonel operating to PJHQ, the mission includes staff and training support to a number of separate organisations working to a common unifying purpose. The Household Division are represented through Commander SST and the DCOS, Major Paul Downes CG who coordinates the J1 and J4 staff effort and training across the missions and wider theatre. The British staff operate within a number of International Community missions including the United Nations (UN), European Union Training Mission (EUT-M), the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) and liaison with the Somali Government and MOD.

With some 65 personnel in theatre, it is a small commitment but one with significant influence and output with workloads to deliver institutional reform and a lasting chance of peace. The majority of the personnel from across the International Community are based in Mogadishu International Airport (MIA). A vast sprawling complex which sits within a narrow strip of land sandwiched between Mogadishu and the Indian Ocean, MIA is the Main Operating Base for all international efforts. It is a thriving mass of diplomats, contractors, soldiers, politicians and NGOs, all working to achieve some sort of resolution and progress whilst representing the interests of their own nations and organisations. For many of the International Community, MIA is the scope of their experiences of Somalia, and they will never be able to interact with the Somali people, nor leave the confines of the secure area. It can be a relatively calm existence for those who call MIA their home; the location sits in glaring contrast to the poverty and violence which is the reality of everyday life on the other side of the HESCO perimeter wall.

Mogadishu International Airport, home to the UK Mission Headquarters in Somalia Mogadishu International Airport, home to the UK Mission Headquarters in Somalia |

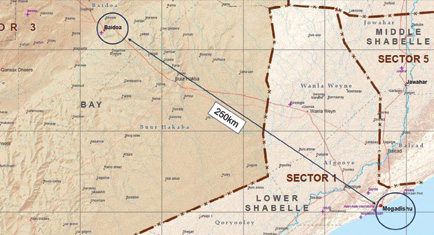

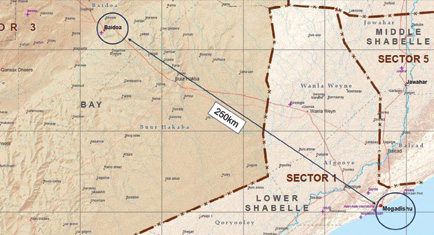

Somalia and the Area of Operations Somalia and the Area of Operations |

The military missions have been more fortunate and we have managed to escape the confines of Mogadishu for the slightly less salubrious surroundings of Baidoa, a small provincial city some 200km inland. Baidoa was once the interim capital of the country at the height of the civil war and is the capital of Southwest State. The complexities of Somali politics and member states are confusing and give further fuel to the rivalries that are the hallmarks of the current problems facing the country. Somali politics are a thesis in themselves and when overlaid on top of the historical ‘clan’ rivalries that have dogged the nation over the years, they add a further dimension to the problems facing the International Community and Federal Government of Somalia (FGS). Baidoa, one of five Federal Member States (FMS) has its own Government with its own Presidential cabinet and ongoing tensions with a Mogadishu based Federal Government. The FGS is often seen as a distant and ineffective body focused on its own influence rather than the good of the wider member states. It is the relationship between the FGS and the FMS that the International Community are focused on, developing in tandem with security sector reform, governance and the provision of the rule of law. In a country where the rule of law and security are a distant memory, the journey in re-establishing even the most basic of security and legal institutions and constitution is a challenge that is both daunting and challenging.

The SNA has a rich heritage and many historical links to the British Army. Somali soldiers served with great distinction in the East African campaigns and the wider theatres of both the Great War and the Second World War. The Somaliland Camel Corps and Somaliland Scouts were both a part of the fabric of British Somaliland and imperial interests within East Africa, and the current SNA can track their history through those antecedent regiments. Whilst our current involvement is benign in comparison, the connection to the present generation of soldiers is very real. As always in these theatres of operation, the ‘occupation of arms’ remains one that transcends cultural and national boundaries, providing a conduit to relationships that will perhaps sow the seed of hope in a land that has been bereft of such an emotion for over three decades.

The simple mission of making the SNA better is of course a naïve statement. Although a blank canvas, it lacks the most basic of military needs. Uniform, weapons, command structures, training organisations, equipment support, doctrine and institutional resilience are all stark in their absence. Whilst the SNA soldier has the grit, drive and potential to provide the bedrock of an effective fighting force, much work is required to develop the potential to an effective military component able to operate in support of the population and its Government. The role of the Somali National Army Support Team (SST) has been to provide the training to develop a nascent capability. The wider British commitment, working in tandem with the training providers, is to equip a battalion of soldiers from 60 Division, with personal equipment (not including weapons) and vehicles, and to build a barracks to accommodate the battalion. Longer term plans will see the training of additional battalions, providing the SNA with the combat power to defeat the Al Shabab led insurgency. In the interim period, our commitment in Baidoa sees 25 personnel training sub units for operations against Al Shabab within Southwest State. The UK SST is supported by an RLC and Intelligence Corps officer with a training team of 22 from a Specialised Infantry Battalion (SPIB) formed from the 2nd Battalion The Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment. The training is based on our own battle craft syllabus, providing the SNA with a standard of training hitherto not experienced within the country. Battlefield first aid, patrolling skills, skill-at-arms, defensive construction and defensive operations, are the main areas and the results have been impressive. Despite the lack of equipment and support mechanisms, the SNA have already used their new found skills to great effect.

The author (centre) and the UK SST in the ruins of Baidoa Airfield The author (centre) and the UK SST in the ruins of Baidoa Airfield |

The idea of British troops deploying to train and fight alongside indigenous forces is not new and was once commonplace in Somaliland with the Somaliland Scouts and Camel Corps and elsewhere. Now, the climate has changed, risk appetite reduced and our actions far more scrutinised. The SPIB concept now gives us the ability to project forces into austere conditions at reach with a degree of autonomy provided through our additional levels of training and support mechanisms. Similar to the BMATT type roles and Battalion Short Term Training Team tasks, the role will develop further, providing opportunities for soldiers and officers from across the infantry. For a young second tour platoon or section commander, there will be great opportunities for adventure and professional development through attachment to a SPIB.

In tandem with the provision of tactical training, our efforts have also been on developing institutional resilience with a focus on the Divisional staff and operational planning. With no equivalent to Sandhurst or the Staff College, individual skills are again lacking. HQ 60 Division is more akin to a battalion headquarters and is certainly not London District. Commanded by a 57 years old brigadier with vast experience of fighting, there is however no real understanding of any formal decision-making process, planning and staff functions. Decisions are made on intuition and acceptance of risk as a part of daily routine. Even the lowest level of operations are often led by the brigadier or his deputy, a colonel. In Somalia, officers are usually commissioned from the ranks or through patronage rather than any formalised selection process. Brave to a fault, but lacking in military education, casualties have been significant and localised success beyond the urban centres are fleeting at best. We have used the current operational laydown and threats as a means to develop an understanding of military planning and to mentor the Divisional staff. This approach has seen some success which has been encouraging for an army which regularly experiences defeat at the hands of a well-equipped and determined enemy.

Using a very basic form of the 7 Questions, the SST has coached the planning staff through a number of planning rounds which are then subsequently executed by the soldiers who have received UK led tactical training. Over a number of months, the team has helped deliver planning processes which have led to the reconstruction of a series of Forward Operating Bases which have enhanced security within the state. Prior to this drive to provide a defensive screen, each of the FOBs had been attacked and overrun by Al Shabab several times in the preceding months. Since this new series of operations, all have been attacked but each time the attack has been repulsed and the positions held. Of particular note has been the development of low-level skills. Skill-at-arms is currently being taught using air rifles due to a lack of weaponry and ammunition. By taking the SNA back to the basics and by teaching the Marksmanship principles effectively, there has been a significant increase in the ability of the SNA to conduct operational shooting.

The top shot on a recent training course was subsequently deployed to a newly constructed FOB at Makuda, some 5km south of Baidoa. Al Shabab subsequently attacked the FOB and the soldier who was awarded top shot with an air rifle killed two enemy with his AK47 at a range of well over 200m. For a country where the ‘Beirut unload’ is commonplace, this advance in shooting skills will have a tangible effect on operational capability and the moral component. Sometimes it is the small victories that have the best results. As the mission progresses so will the abilities of the SNA and the wider Somali MOD. We have now started to deliver our first Company Collective Training course in September which will provide the first of three Company Groups, trained and equipped within this financial year. As the force densities increase, so will the SNA’s ability to clear and hold ground from the Al Shabab threat and thereby sow the seeds for potential peace.

Somali Soldiers undergoing training |

There remains much to be done in Somalia, this will not be a quick fix and the commitment from the International Community can be fickle. It is the long-term commitment to institutional reform and security sector reform that is so vital in providing a legacy effect to this country where war and violence are the norms. The challenges remain significant and without continued comprehensive reform of governmental institutions, enduring success will remain an over the horizon aspiration. Training, heavy weapons, equipment support, doctrine and robust planning processes are all vital to military development and the defeat of Al Shabab. There is now, however, the potential, and the efforts of the UK military across each of the Somali focused missions are vital.

Despite the years of famine, war and violence, Somalia and the Somali population remain resolute. Fascinating and frustrating in equal measure, there are undoubtedly the signs of a burgeoning peace and improved prosperity. Somalia has for three decades been defined by violence and suffering, there is now a sense of hopefulness and perhaps that might be the theme that defines the next three decades – our continued commitment will be pivotal.

|

|

Mogadishu International Airport, home to the UK Mission Headquarters in Somalia

Mogadishu International Airport, home to the UK Mission Headquarters in Somalia Somalia and the Area of Operations

Somalia and the Area of Operations  The author (centre) and the UK SST in the ruins of Baidoa Airfield

The author (centre) and the UK SST in the ruins of Baidoa Airfield Somali Soldiers undergoing training

Somali Soldiers undergoing training