|

Dr The Honourable Gilbert Greenall CBE

formerly The Life Guards

In conversation with The Editor

|

Gilbert Greenall and I are the same age, and yet Gilbert left The Life Guards before I had even joined, to follow a career that neither he nor his friends could have predicted. As a young officer, Gilbert had flown aeroplanes and driven fast cars, and was once pursued in his Porsche by the police across northern Germany. He had a rebellious approach to life, was easily bored by peacetime soldiering, and as a rich and privileged young man, his future was already planned. A few years in the Regiment, followed by the family business. But it was not to be.

‘Leaving school just before my eighteenth birthday, I had always wanted to join the Army’ before going into the brewing firm, Greenall & Co. He started at Brigade Squad in 1973, then Sandhurst. He still has his tactics and leadership manuals from there; ‘on the second page of one of those volumes is Clausewitz’s principles of war, and they have remained in my head since that first week at Sandhurst’. Looking back on his 30 years as a Combat Civilian (the title of his recently published memoirs), he concludes that ‘many of our trials and tribulations have come from not obeying Clausewitz’s principles of war’.

Gilbert was posted to The Life Guards in Detmold, Germany and those early days were a little disappointing. ‘I hadn’t really anticipated how short of money we were, with the limited track mileage’ for exercises and the chronic shortages of training ammunition. Then, Northern Ireland in 1974, a more challenging environment for a young 19-year-old officer. He recalls the frequent and edgy incidents, together with the unnerving repetition, like setting off for patrol every day through the same camp gates, ‘a difficult thing to do’; there was plenty here to focus the mind.

The Prime Minister, John Major, Gilbert Greenall, and Major General Mike Jackson, in the early days of the NATO mission in Bosnia, 1996, following the signing of the Dayton Agreement

The Prime Minister, John Major, Gilbert Greenall, and Major General Mike Jackson, in the early days of the NATO mission in Bosnia, 1996, following the signing of the Dayton Agreement |

The forbidding Mostar Road, Bosnia 1992

The forbidding Mostar Road, Bosnia 1992 |

Back in Germany, he attended junior officers’ education courses, and wrote an essay that caught the eye of the local education officers who asked him to consider taking up a place at Oxford. It was ‘very tempting’, and he still has a few regrets about turning it down, but it would have committed him to five more years in the Army, while the pre-ordained plan was sending him in another direction: two and a half years learning about the family business. Most of this proved rather dull, although he did spend time in France and Germany, in the vineyards and improving his language skills. And then an entirely different possibility emerged. He met some friends at INSEAD, the graduate business school just outside Paris, and despite having no degree, they encouraged him to ‘just apply and see what happens’. He did, and when he ‘proudly announced his success to his father, he was told ‘if you do that, there will be no place here’ ….they will fill your head with silly ideas and I am not having those brought here’. ‘I suddenly found myself without that opportunity …. so that was the end of that’.

For Gilbert, it was a good time to be at INSEAD, in the mid-70s when the study of economic and population growth was turning to the issue of resources and their finite supply. The Brandt Report and The Limits to Growth were focusing on some ‘off centre’ subjects like international development, managing natural resources, the use of ‘appropriate technologies’, etc., all mainstream issues 40 years’ on. Gilbert was intrigued by this new thinking.

It was now 1979, Gilbert had left INSEAD, and unlike most of his fellow students, had not yet found a job, so decided to take a trip to Thailand to see an ‘appropriate technology’ project being run by an INSEAD graduate in Bangkok. It proved not to be the idealistic endeavour that Gilbert had expected. Slightly crestfallen, he had a chance meeting with a Swiss doctor in the Oriental Hotel bar, to be told about the desperate situation along the border with Cambodia. ‘There are dark things going on there’, with thousands of Cambodians fleeing into Thailand, escaping from the Khmer Rouge. ‘Volunteers are needed; why don’t you come’ … ‘So off I went, and that was really the beginning of my involvement with humanitarian emergencies’.

When he arrived at the Cambodian border, Gilbert saw human suffering on a scale he had never experienced, a parallel world of chaos and misery that shocked him deeply. The aid agencies in Bangkok claimed that all was under control, but Gilbert could see that this was far from the case. There was no management structure, no overall leadership, and no one trying to pull all the activity together to help these refugees. Gilbert knew he was not ready for a desk job, he had some management training, ‘and this was much more exciting’. Working in this chaotic environment, relying on ‘one’s diplomatic and political competence to get things done’; perhaps a rather romantic and quixotic idea at the time, but for him it was a ‘damascene moment …. A life-changing event….’. As he says in his book ‘I had found my career’, albeit one that promised no professional status and minimum, if any, remuneration. Perhaps this road less travelled that he had chosen also addressed another incentive for this privileged young man. As he says, ‘the problem with inherited wealth is that you never feel quite that you did it yourself’. Here was the chance to do just that, albeit in rather an unusual way.

Back home, Gilbert applied for a job in Oxfam, ‘the biggest challenge of my life’ which required overcoming prejudices while wondering ‘what on earth will all my friends think about this?’. He recalls a scene in the film Apocalypse Now, when Captain Willard ‘is looking through the Colonel’s cv, and suddenly it does a right-angle turn’, the kind of turn that ‘makes all your friends think you have gone entirely bonkers’. But this is where the comparisons with the renegade Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando) thankfully end! In Gilbert’s case, he was to ‘disappear off to Africa for fifteen months’ to run the Oxfam operation in Uganda, tackling famine and suffering. It was his natural rebelliousness, compassion, and optimism that sustained him, along with determination and courage. ‘We live in our tribal redoubts, and this was a big challenge’.

Gilbert started in Uganda on his own, building a team that eventually grew to 14 international staff and 80 African locals. There was a civil war going on, the country was in a mess, and the immediate challenge was to distribute food to the famine areas of north eastern Uganda, in a place where getting around was difficult, and ‘with people shooting at you fairly frequently’. It was a huge undertaking, and yet within a month he was running six distribution centres.

Despite the dangers in Uganda, Gilbert felt strangely ‘safe for most of the time, even when a child leapt up 12 feet away with an AK 47 and fired the whole damn thing at me’. It was only when he went home for Christmas and then returned that reality kicked-in; from then on, he started to worry that he wouldn’t survive to the end of each day. His carefree bravado may have left him, but he finished the tour, reflecting on what he had learnt about international development and the delivery of humanitarian aid in places where the essentials of life simply do not exist. He had also seen for himself that the obvious is not always the best; for example, food hand-outs are a short-term expedient, but not the solution. Uganda also taught Gilbert about other challenges, like the maelstrom of government and non-government agencies (NGOs), all with their own agendas and ambitions. Working among them is not easy.

Gilbert realised after this first mission that being an unpaid volunteer was not a viable long-term career move; but he still needed to do something that would satisfy his desire to help others. In Uganda, he’d been impressed with the work of the Save the Children Fund and their medical staff, reasoning that perhaps one ‘can narrow the focus down from a 100,000 to one person’, by qualifying as a doctor. He spent the next seven years at Bristol University and doing his house jobs, and then, just after Christmas 1990, he went to an Old Etonian Medical Society dinner, where a consultant from Great Ormond Street spoke passionately about the plight of the Kurds in Northern Iraq, fleeing from Saddam Hussein’s forces. ‘Who is going to put their hand up to go to Iran next week?’ Gilbert’s next job, in the A&E at Cheltenham General Hospital, was not until August, so his hand went up. The next day he contacted the British Red Cross and was soon en route to north-west Iran to conduct a humanitarian assessment of the situation along the Iraqi border.

There was now a growing humanitarian crisis as the Kurds made their way across the border in the mountainous regions of Northern Iraq, and into Iran. Gilbert wrote his report, concluding that the solution lay not in Iran, which had its own challenges, but back in the indigenous Kurdish region of Iraq. His timing was perfect, since a senior civil servant in the Overseas Development Administration in London, (now the Department of Overseas Development - DFID), had concluded the same, and Gilbert’s report provided the first-hand evidence that he needed.

The decision to establish safe havens for the Kurds in Northern Iraq was a watershed, both for the international community and Gilbert. The military were now involved, and Gilbert was to play a vital role in managing the humanitarian operation while 3 Commando Brigade Royal Marines created and secured the safe havens. Although, as Gilbert says, there had been support to civilian populations in the aftermath of the Second World War, the military had ‘no institutional memory’ since ‘with the advent of nuclear war and the use of tactical nuclear weapons, civilians were not going to exist … they would all be dead’.

It is strange to understand this now, in an era where war is fought amongst the people, but this does reflect the Cold War thinking that many of us grew up with; based on the concept of deterrence and the hope that we would never have to face the aftermath of a nuclear war. But with the Cold War over, Operation Safe Haven was the perfect primer for what could be achieved, although at the time not everyone agreed. The NGOs wanted their independence, and, as Gilbert says, the ‘military leadership was split down the middle. There were those who talked about the ‘blunting of their swords’ while others acknowledged that victory was now going to look different and more complicated. ‘These would not be wars of existential survival…we won’t be using overwhelming force because we won’t win the peace’.

Gilbert had a proper role. He was a civilian, a doctor, a former soldier, and now an adviser on humanitarian operations, with a seat at the brigade commander’s bird-table. Although he had never been in a brigade headquarters, he knew something of the military culture, where the lines were to get things achieved, and the polite and courteous way the chain of command works. He could now achieve his aims on an unprecedented scale, like the delivery of 50,000 tents in a week. The mission was an immense success, the military shifted their thinking about humanitarian operations, Gilbert was on the lecture circuit alongside the Safe Haven commanders, and military exercises began to weave the so-called ‘white cell’ dimension into their scenarios. Military operations were no longer just about the enemy.

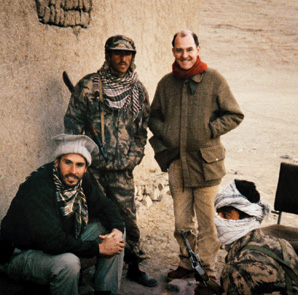

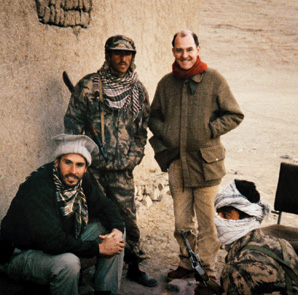

Gilbert Greenall, on the way to Bamian, in central Afghanistan. 2001

Gilbert Greenall, on the way to Bamian, in central Afghanistan. 2001 |

The launch of Gilbert’s book, Combat Civilian, at the Cavalry & Guards Club. 25th September 2019.

Back row. Left-to-right. Lieutenant General Sir Bill Rollo, Lieutenant General Sir John Kiszely, Major Harry Bucknall

Front row. Left-to-right. Gilbert Greenall, Baroness Chalker, and General the Lord Richards (who once introduced Gilbert to his MoD staff by saying ‘This is Gilbert Greenall; he is my combat civilian’)

The launch of Gilbert’s book, Combat Civilian, at the Cavalry & Guards Club. 25th September 2019.

Back row. Left-to-right. Lieutenant General Sir Bill Rollo, Lieutenant General Sir John Kiszely, Major Harry Bucknall

Front row. Left-to-right. Gilbert Greenall, Baroness Chalker, and General the Lord Richards (who once introduced Gilbert to his MoD staff by saying ‘This is Gilbert Greenall; he is my combat civilian’) |

The next challenge, in early 1992, was the Bosnian War, a complicated, protracted and ghastly civil war. Gilbert was there at the beginning, working for the ODA, and seeing some of the flaws in the original UN mandate. Soldiers, with their blue berets, limited resources and narrow rules of engagement, were being drawn into a situation with which they could not cope, when ‘peace-keeping’ became confused with a forlorn attempt at ‘peace-making’. An impossible scenario, since there was no peace to keep and no means to enforce it.

Gilbert was there during the Siege of Sarajevo in 1992-93, and one of his memorable achievements, well described in his book, was the ‘proving of the road’ from Mostar to Sarajevo. The UN had deemed the road ‘out of bounds’ and far too dangerous, and as Gilbert says, ‘once a road is closed, you could be there for years trying to get it reopened’. But he and the UNHCR Chief of Operations had other ideas: they decided to drive the 179 km to the coast to show that the road could be used for supplying Sarajevo. With fallen trees across the road, and no other vehicles around, they made it to the UN office in Split, via the war-torn city of Mostar, announcing that the journey had taken three hours, not the official 14 hours through the mountains; and they were simply not believed. The UN in New York immediately confirmed that there would be no change in policy; the road would stay closed.

Then Gilbert had some luck, discovering the next day that Lynda Chalker, Minister for Overseas Development, was coming to Zagreb, and that he was to organise a programme for her, including a visit to the ODA convoy teams. ‘What about a trip down the Mostar road?’ he asked his boss back in London. Gilbert remembered being the Visits Officer back in the Army, but this was on a different scale. If the visit went well, with the minister escorted down part of the Mostar road without mishap, then the UN would need to review its policy. But if it went wrong, and there were plenty of FCO ‘rumbles’ about the idea, the consequences would be dire.

At the launch party for Gilbert’s book in early September this year, I met Baroness Chalker and reminded her of that visit. ‘I knew I had to do it’, she said, and there was indeed much riding on its success. And as Gilbert says ‘Lynda had the courage to do it … I really do admire her because it was the only way to break the logjam. In the UN, process is everything…. And yet the outcome for the Bosnian war’ following the minister’s drive down that road ‘depended on that one single thing’. Sarajevo did not fall to the Serbs, the Moslems strengthened their positions, and finally NATO arrived with the military mandate that the UN lacked.

NATO took over the mission in early 1996, following the signing of the Dayton Agreement, and this was another important turning point in the concept of international development and delivering humanitarian assistance as a means of bringing peace to a troubled region. Gilbert now had a more clearly defined job, working within a British-led divisional headquarters, and he also had commanders, like Mike Jackson and John Kiszely, who ‘got it’. They understood that getting the infrastructure working again, such as the water supply, communications, electricity, etc, were legitimate tasks to which the military could contribute. They were a vital part of winning the peace, and Gilbert became a key facilitator in identifying and approving projects and finding the resources to make them happen.

That period in Bosnia in the mid-90s was a highpoint in Gilbert’s 30 years as a combat civilian, and it seemed then that the international community, working closely with the military where that made sense, had found a workable and practical way of providing humanitarian assistance as a means of delivering real effect on the ground. However, things did not get easier with the passing of time, and some of the valuable lessons from Bosnia were to be lost. With a new government in 1997, and a separate department of state, (DFID) with a large and relatively independent budget, and the even more protracted conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, overseas development just became more complicated, challenging, and frustrating. In the latter part of our conversation, Gilbert alludes to the times in more recent years when the unity of effort and pragmatism that he had experienced in the past had diminished. Institutional failings and muddled thinking about a desire to ‘do good’ with social development programmes has not helped.

Once a Life Guard, always a Life Guard!

Once a Life Guard, always a Life Guard! |

Gilbert’s career as a combat civilian has continued nonetheless, and over the last 20 years since Bosnia, he has spent time in almost every conflict zone around the globe, including Albania, Kosovo, East Timor, Gaza, Libya, Afghanistan, and most recently Iraq, with a few others in between. Gilbert has an innate sense of what is the right and proper thing to do to reduce human suffering around the world, but he is also a realist. As he says in the concluding paragraph of his book, looking back over his extraordinary career ‘I regret the loss of opportunity to travel alone when the concept of neutrality still held, to have had the goodwill of all sides to a conflict, and hopefully to have achieved some lasting good’.

However, it would be wrong to end here with these reflective words since they imply that Gilbert is about to put up his feet and do other things. While he might regret, as many do, some of the failings of the last 20 years in terms of ‘winning the peace’ and making the world a better place, he still thinks there are opportunities to re-learn some of those lessons and apply them in the future; and he is very keen to play his part. As he implies towards the end of our conversation, it is still not too late, provided that our political leaders and policy-makers focus their minds.

There is a great line in Bridget Jones’s Diary when Bridget describes Mark Darcy (Colin Firth) as ‘a bit of a hero really’. Gilbert may laugh or be embarrassed at the comparison, although he might prefer this one to Colonel Kurtz! Either way, if the definition of a hero is someone who has a choice about placing himself in harm’s way time and time again to help others, then Gilbert fits that definition. Read Combat Civilian to understand why.

Gilbert’s Greenall’s book is reviewed on the website here.

|

|