|

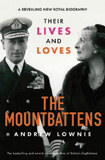

The Mountbattens

Their Lives And Loves

by Andrew Lownie

|

When a new book is published about someone already lavishly furnished with biographies, both authorised and unofficial, and where no new documents have been uncovered or released in the interim, the reader is bound to ask the question ‘why bother?’ In the case of the recently published The Mountbattens, the answer lies in the second half of the book’s sub-title: Their Lives and Loves. But therein lies the problem. The headline-grabbing sub-title hinting at salacious allegations about the bedroom-based activities of Admiral of the Fleet Earl Mountbatten of Burma (known to Life Guards as ‘Colonel Dickie’) and his wife, Edwina, can only be justified on historical, as opposed to commercial, grounds if such highly marketable revelations are both relevant and true. When a new book is published about someone already lavishly furnished with biographies, both authorised and unofficial, and where no new documents have been uncovered or released in the interim, the reader is bound to ask the question ‘why bother?’ In the case of the recently published The Mountbattens, the answer lies in the second half of the book’s sub-title: Their Lives and Loves. But therein lies the problem. The headline-grabbing sub-title hinting at salacious allegations about the bedroom-based activities of Admiral of the Fleet Earl Mountbatten of Burma (known to Life Guards as ‘Colonel Dickie’) and his wife, Edwina, can only be justified on historical, as opposed to commercial, grounds if such highly marketable revelations are both relevant and true.

For example, there can be no question that the late Jimmy Savile’s aggressive and well-evidenced paedophilia, shamelessly ignored by the authorities, informs to a considerable degree any account of his life and must be included. Similarly, the gratuitous but verifiable disclosure in court of Sir Roger Casement’s true sexuality was undoubtedly used to ensure his march to the scaffold on 3rd August 1916 and so must be included in any biography.

But in the case of the Mountbattens, are the unverifiable, hearsay stories contained in Mr Lownie’s new book, to the effect that they both regularly ‘played away from home’ and may even have ‘batted for the other side’, either true or relevant? Or have they only been included to ensure a profit for the publisher in a prurient age in which ‘sex sells’?

The answer to the truth question begs another: in the absence of documentary or first-hand evidence, ‘were you under the bed at the time?’ The response by Mr Lownie and the others he cites is, of course, ‘no’. So, all the allegations, most of which have been aired before, are matters of speculation and cannot be proved even by circumstantial evidence: the boasts of people quoted in the chapter entitled Rumours are nothing more than that. Nonetheless, some if not all of the stories may be true.

The Mountbattens certainly lived apart for much of their married life and had the opportunity and the motives for infidelity: Edwina, who held the purse strings in a tight grip, was (on account of her nouveau riche, mittel-European antecedents on her mother’s side) socially insecure, selfish, self-centred, haughty and almost certainly serially unfaithful to her husband; Dickie, who was vain, ambitious, charming, craved adoration and relied on his wife’s money to fund his career and lifestyle, probably reciprocated in kind but not to the point where he endangered the marriage, he having less leverage over the mutually beneficial continuation of the relationship than his wife. So, if the allegations are true in whole or in part, are they relevant?

With the possible exception of Lady Mountbatten’s relationship with Nehru, the answer must be ‘no’. The alleged hurly-burlies played out on the Mountbattens’ various chaises longes or in the deep, deep comfort of their various double beds (to paraphrase the sexually-liberated Edwardian actress, Mrs Patrick Campbell) have not been shown by Mr Lownie, or any of the other Mountbatten biographers, to have played even a minor part in their public lives; excepting, perhaps, the much featured but unproved liaison with Nehru.

So, whether or not Lady Mountbatten had a requited passion for a succession of men of colour before the Second World War had no relevance whatsoever to her outstanding work as a humanitarian both during and after the war. Her extra-marital love affairs, if true, were an expression of her need for independence, control, self-gratification and were probably an expression of her essentially selfish nature.

The same can be said of Dickie, whose dalliances with both sexes, again if true, had more to do with his constant craving to be loved and admired, rather than as a means of furthering his career. Indeed, the public exposure of his sex life, real or imagined, would, even in the Swinging Sixties, have been damaging to his reputation and, in earlier times, disastrous to his career. That he reached almost the pinnacle of power without a whiff of public scandal cannot be ignored when addressing the relevance of his sexuality. During his lifetime, Mountbatten made many enemies who, had they had the material to bring him down, would undoubtedly have done so in much the same way that the Duke of Westminster was able to hound his brother-in-law, Earl Beauchamp, out of the country in 1931. When told that his Master of the Horse was bisexual, King George V famously remarked that he thought ‘that men like that shot themselves’, a remark only surpassed by Lord Beauchamp’s wife who famously said ‘Bendor tells me William is a bugler [sic]’.

For the rest and barring some inconclusive reappraisals of Dickie Mountbatten’s roles in the Royal Navy, at Combined Operations and as Supreme Commander South East Asia, The Mountbattens is largely a retelling of a well-known story: more Downton Abbey than the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. But it is well-written and makes good bedtime reading, albeit that it’s eventual resting place is likely to be in what Colonel Dickie would undoubtedly have referred to as ‘the heads’.

Christopher Joll

Blink Publishing. www.blinkpublishing.co.uk

|

|