|

BY THE SPREADING OAK TREE

A GUARDSMAN’S VICTORIA CROSS - 1944

by Harry Bucknall

formerly Coldstream Guards

|

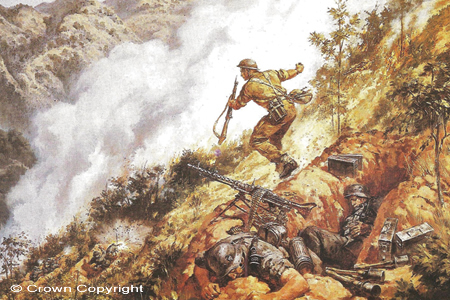

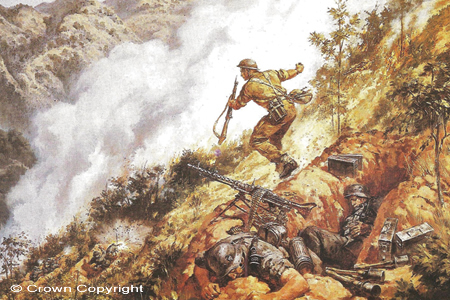

CSM Peter Wright VC

|

This excerpt from ‘Like a Tramp, Like a Pilgrim’, Harry Bucknall’s book about his 1,400 mile walk from London to Rome in 2012, does not appear in the final published version. The author, who has been on the road for nearly three months by this stage, is 77 miles short of his destination, Rome …

Not long after San Antonio, the Via Cassia began to climb gently and just before a sharp left hand bend I noticed the prominent green and white sign of a Commonwealth War Grave Cemetery; siren like it called to me.

I walked down the path until I reached a pretty headland overlooking the great expanse of the Lago di Bolsena, a more tranquil place I could not imagine. At the centre of the immaculately tended tableau, burial site to over 600 Allied servicemen, a spreading oak tree swung gently in the breeze that blew in off the lake. I laid my rucksack down by the hedge and made my way down the rows of stark white graves, Grenadier, Coldstream and Scots Guardsmen who had died while serving as part of 24 Guards Brigade - some of whose names I recognized - lay alongside Indian, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand and South African comrades.

The campaign in Italy had been bloody and ferocious, not only was the mountainous terrain arduous but the Wehrmacht’s fight was spirited. By the winter of 1943, the Allied advance had as good as faltered about the Gustav Line, a series of enemy defences that spanned the Italian peninsular south of Rome, centred on the Abbey at Monte Cassino which would eventually fall on 18th May 1944, enabling General Alexander, the Allied Commander in Italy, to exploit the Nazi withdrawal and liberate Rome on 4th June 1944, just two days before the D-Day landings in Normandy. Siena fell in early July and by the end of the month, the Eighth Army under the command of General Oliver Leese was knocking on Florence’s door. It was little surprise then that Alexander, an enormously civilized Irish Guards officer with great style and panache, should have chosen the field where I now found myself as the site for his advance headquarters.

For a moment the place was again a hive of activity under a laced canopy of shimmering camouflage nets as tents echoed to the flutter of radio traffic, generators hummed away providing much needed power to caravans filled with eager staff officers poring over maps while authoritarian red-capped Military Policemen controlled the constant flow of motorbike dispatch riders, jeeps and lorries ferrying soldiers back and forth.

Of the important visitors that late July in 1944 were two Generals by the name of Lyon and Collingwood. Neither of them existed; these were the code names for King George VI who, over a number of days that summer, travelled the length and breadth of Italy visiting Allied troops. No matter whether resplendent in Naval whites with the Mediterranean Fleet off Naples or in khaki bush jacket and shorts being driven through the countryside perched on the rear of his Humber Staff Car for all to see, the visit of this popular and much loved monarch, would have been a great boost to morale at such a critical time.

To give an indication of the intensity of fighting in the preceding months, while in Italy, George VI awarded no less than four Victoria Crosses that August.

I wondered whether it was also on this visit that General Alex spoke to His Majesty about Company Sergeant Major Peter ‘Misty’ Wright of Number One Company, 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards, who, in September 1943, was part of an assault on a well-defended hill North of Salerno. With most of his officers either killed or mortally wounded, the attack faltered until Peter - then at the rear with the stretcher-bearers - went forward, took command and, in an act of outstanding heroism and magnificent leadership, personally dispatched the first one, then a second and finally a third Spandau machine gun position using nothing other than the grenades he had to hand and his bayonet. After, he rallied the remnants of his company onto the ridgeline, despite the continued heavy bombardment, consolidated their position and, repelled a counter-attack until relieved the following morning by the Scots Guards. General Alexander awarded CSM Wright an immediate Distinguished Conduct Medal in the field. I had the privilege to know Peter, who, after the war, returned to Suffolk to farm; he was a kind, gentle man, who I genuinely do not believe had a bad bone in his body.

The story however does not end there. I imagined that, back in his headquarters, His Majesty and the General might have sat under the shade of a tent awning, taking a break while reflecting over a tumbler or two of something invigorating. The sun going down over the lake, talk perhaps turning to happier events, news of home and family and then in a pause, did Alexander mention that he felt Wright’s bravery warranted the highest gallantry award. Did King George VI agree and, on his return home, give instructions that the Company Sergeant Major’s medal was to be substituted for the Victoria Cross - which was actually presented at an investiture in London that November; perhaps the only time in history that this substitution has ever happened. I wonder if anyone knows? Peter would later chuckle to me, how no one ever asked for the other medal back.

Back at the gate, I took one last look over the Cemetery - the Fallen at peace. It was a blessed spot.

Like a Tramp, Like a Pilgrim, by Harry Bucknall, is reviewed in the Autumn 2014 issue of The Guards Magazine, and is published by Bloomsbury, price £16.99.

CSM Peter Wright winning his VC at Point 270 on the Capella Ridge near Salerno.

Painted by Peter Archer in 1988

|

|

|